New Zealand's affordable housing situation is failing to improve to meet ever-rising demand. With the most unaffordable housing market in the OECD and 25% of families spending 40% of their disposable income on housing, the need for innovative solutions has never been more urgent. Sam Stubbs, Managing Director of Simplicity, believes he has found a path forward — one that challenges conventional thinking about housing as both an investment and a social necessity.

The investment case for housing

Sam's approach begins with a fundamental premise: housing is not just a social good, but an exceptional investment opportunity. "You and I will always pay the rent or the mortgage," he explains. "We need a roof over our head. It's the last bill you won't pay."

This insight drives Simplicity's entry into the build-to-rent market. As a non-profit owned by a charity with a 100-year outlook, Simplicity can afford to think differently about housing investment. Where traditional developers focus on quick sales and maximum short-term returns, Simplicity builds for the long haul.

The company's apartments are built to last at least 100 years — double New Zealand's 50-year building code minimum, and they cost around 30-40% less to build than comparable properties.

Rethinking risk and scale

The traditional view of residential property as a high-risk, speculative asset class is fundamentally flawed, according to Sam. When approached with long-term thinking and sufficient scale, housing becomes "a little like a government bond in terms of risk... if you own one or two investment properties, it's risky. If you own 10,000 of them, any one thing that happens is almost irrelevant."

The key is diversification and quality. This principle extends to community housing bonds, which Simplicity views as having government-like security due to rental housing subsidies that are politically impossible to remove.

However, the finance industry's conservative nature creates barriers to innovation. "If you bespoke it, if you make it difficult to understand, if you layer lots of complexity, finance industry runs away because it's so easy just to lend to another homebuyer." The solution is making new housing models "look and feel like any other investment" — repeatable and familiar.

The economics of scale

New Zealand's housing industry suffers from a peculiar contradiction: it's the country's largest industry operated like a cottage industry. He explains "Everything is so small scale and bespoke because everyone wants their tile, their tap, their layout."

When Simplicity's building partners first started construction, they used 27 different types of windows and doors. Today, they use just seven. This standardisation, combined with volume purchasing power, creates dramatic cost savings. "When you're building hundreds a year, then you're a price maker."

The comparison with Canada is striking. Building a house in Calgary — a city similar in size to Auckland but with harsh winters requiring superior thermal performance — costs about half the price of Auckland construction. Sam emphasises — "There is no rocket science in this".

Breaking the finance bottleneck

The path to large-scale housing development requires patient capital — something the current banking system, with its focus on short-term returns and owner-occupier lending, isn't structured to provide. Banks hold over 60% of their loan books in residential property, yet remain reluctant to finance innovative housing solutions.

Simplicity's advantage lies in accessing KiwiSaver funds and other long-term investment pools that can match the investment horizon of housing assets, bypassing traditional banking constraints. Internationally, pension funds routinely invest in build-to-rent and social housing, viewing it as a stable, bond-like investment.

The government could accelerate this process by providing funding certainty. Rather than paying over $2,000 per week to house families in motels, the government could support the construction of apartments that rent for $600 per week and generate positive returns for investors.

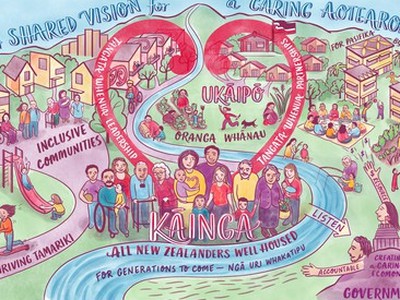

Redefining the New Zealand dream

The traditional New Zealand dream of owning a standalone house on a quarter-acre section is becoming increasingly unaffordable and environmentally unsustainable. Sam argues for expanding the definition of a home to include quality apartment living and long-term rental arrangements.

"42% of people in the OECD live in an apartment, only 4% of New Zealanders do," he notes. The reluctance to embrace apartment living stems partly from poor examples, but also from cultural expectations.

Long-term rental arrangements can provide the stability traditionally associated with home-ownership, while freeing up capital for more productive investments. Sam cites a Berlin example where the same family had rented from a pension fund for three generations, treating the apartment as their home with full security of tenure.

The social imperative

Beyond economics, he sees housing as fundamental to social cohesion. "The seeds of revolution are sown in inequity," he warns. Without stable housing, children lack the foundation for educational success and social mobility. "If you don't have money, you don't have choices in life. If you don't have choices, you don't have dignity."

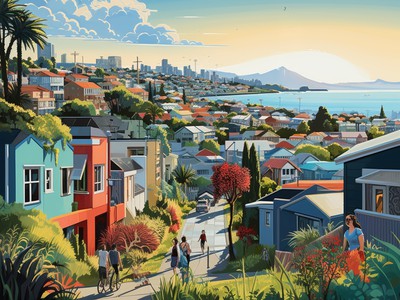

The connection between housing and social stability drives Simplicity's approach to community development. Their high-density developments reserve one-third of land for buildings, one-third for green space, and plant 60 trees per apartment. They also plant a native tree somewhere in New Zealand every week for each apartment they rent.

Government's role in market signals

While market failure in affordable housing is evident, Sam believes the solution lies not in direct government provision but in clear, consistent market signals. "The biggest chequebook in town in any democracy is the government," he notes. "The government has not been sending the signals to the building industry: this is what we want, this is when we want them delivered, this is what we're prepared to pay."

The volatility in housing policy creates uncertainty that prevents private companies from investing in capacity and achieving economies of scale. Multi-decade contracts with consistent demand would enable the private sector to deliver affordable housing at scale.

A scalable solution

Simplicity's model demonstrates that New Zealand's housing crisis is solvable. By combining long-term thinking, economies of scale, patient capital, and quality construction, they've created a template that others can follow. The company provides its intellectual property free to anyone wanting to replicate their approach.

Sam concludes — "We're determined to fight to make that happen and we're absolutely convinced you can... we now have a working model which shows it's possible and we just want to make that available."

The path forward requires courage from policymakers, patience from investors, and a willingness to challenge conventional wisdom about housing. But as Simplicity demonstrates, the tools to solve New Zealand's housing crisis already exist. The question is whether we have the will to use them.