As housing affordability reaches crisis levels across every region in New Zealand, a proven but underutilised tool sits waiting in the policy toolbox. Chris Glaudel, a housing policy expert with decades of international experience, makes a compelling case for why Inclusionary Housing, or Inclusionary Zoning as it is often known, should be embedded in the country's current legislative reforms.

Global Inclusionary Housing benchmarks

National and local set-aside requirements (typical %)

Sources: OECD / Lincoln Institute of Land Policy / CHA Research Dataset / National Planning Frameworks

| Country |

Typical % |

Notes |

Scope |

| Europe |

|

|

|

| Austria (Vienna) |

≥ 66% |

Strongest model; built into zoning |

Local |

| Germany |

30–50% |

City-level. Major projects only. |

Local |

| Switzerland (Zurich) |

≈ 33%; ≥ ⅓ zones |

Cooperative and non-profit focus |

Local |

| Netherlands |

30–40% |

Mix of social and intermediate housing |

Local |

| Finland |

≈ 55% |

Social + Intermediate (≈ 55%) |

Local |

| United Kingdom |

10–40% |

London often 35–50%. |

National |

| France |

20–25% |

National law with penalties |

National |

| Portugal |

Up to 25% |

Local pilots; national plan emerging |

Local |

| Denmark |

Up to 25% |

Uses city-owned land |

National/Local |

| Luxembourg |

10–30% |

Mixed delivery approach |

National/Local |

| Italy |

10–20% |

Linked to city planning rules |

Local |

| Ireland |

Up to 10% |

Long-standing; under review |

National |

| Americas |

|

|

|

| Columbia |

Up to 30% |

Clear affordability tiers |

National/Local |

| United States |

10–20% |

Widely variable; strongest in CA & MA |

Local |

| Chile |

10–20% |

Regional variation |

National/Local |

| Canada |

5–25% |

Major cities leading change |

Local |

Understanding value capture

When Chris Glaudel talks about Inclusionary Housing, he's careful to cut through the jargon that has plagued discussions around this policy instrument. At its core, Inclusionary Housing is about ensuring that when property values increase due to public investment, whether in infrastructure, transit, or planning changes — some of that windfall benefit flows back to serve community needs rather than remaining entirely in private hands.

"The classic examples of land value capture are, say, when a community invests in large-scale transit projects," he explains, pointing to Auckland's Central Rail Link as a prime example. When stations open and thousands of people pass through daily, surrounding properties gain tremendous value through no effort of the landowners themselves. Inclusionary Housing policies capture a portion of that uplift specifically for affordable housing.

He notes "Those landowners did nothing to create that value. It was a change of government policy that created more value by being able to put more units and higher densities onto that site."

The concept isn't theoretical. Chris draws on his experience in California's San Francisco Bay Area, where mass transit improvements came with zoning requirements around stations. Transit-oriented developments set aside portions of the captured value for affordable housing, ensuring that public investments benefited all income levels, not just those who could afford market-rate housing.

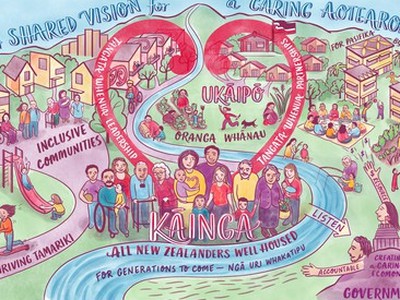

Queenstown's blueprint for affordable communities

In New Zealand, registered Community Housing Providers represent the natural recipients of land or monetary contributions from Inclusionary Housing schemes. Queenstown Lakes District offers the clearest local example, with a single registered provider working seamlessly with the council on an Inclusionary Housing programme that has operated successfully for nearly two decades.

The key, Chris emphasises, is starting with a clear understanding of community need. He asks "Who's not being well-served and is not having access to affordable or accessible housing?" The answer shapes everything else — from which providers to work with to what housing types to prioritise.

"It could be housing for older people, retirees who in New Zealand on superannuation just can't afford market rents. Or it could be specific populations, multi-generational housing, persons with disabilities."

Location matters tremendously in this equation. Sites near schools and employment suit multi-generational families. Properties close to hospitals and age-friendly facilities work better for retirees. Matching the right provider with the right site, based on genuine community need, creates housing that actually serves people rather than ticking policy boxes.

Learning from successes and failures

Chris first encountered Inclusionary Housing in the mid-to-late 1990s while working in California, where the concept had already been in place for one or two decades. The varied outcomes he witnessed taught him crucial lessons about implementation. He states "It's an instrument that can help when well done and well designed," he notes carefully. "It's an instrument that could also, if poorly designed and implemented, create backlash and not work."

Some California communities, particularly wealthy enclaves, adopted programmes deliberately designed to fail, complex, unworkable policies that technically fulfilled state requirements for affordability programmes while ensuring essential workers would continue commuting in rather than living locally. The lesson is clear: context matters, and policies must be genuinely tailored to local conditions rather than copied wholesale. He notes "You just can't lift and shift something, even within California that worked in one community and take it to another."

The critical role of national frameworks

This tension between local adaptation and standardisation points to one of Chris's key arguments: New Zealand needs clear national enablement with local flexibility. Over his 12 years working in New Zealand housing, he's seen the lack of such frameworks identified repeatedly as a barrier. The old Affordable Housing Enabling Territorial Authorities Act (AHETA) laid out a national process but was rescinded before anyone could use it.

Community Housing Aotearoa's research, detailed across three papers, proposes a two-tier system. National legislation would provide clear enablement for local authorities, with regulations specifying how programmes function. The high-level requirements would include housing needs assessments, clear linkages between needs and actions, and crucially, feasibility studies to ensure development isn't shut down.

"Private development has a tremendous role to play," he stresses. "The major role in providing good quality housing for New Zealanders will always come from the private sector, and Inclusionary Housing only works when the private sector is building."

The proposed national framework would standardise basic instruments across Queenstown, Auckland, and Rotorua whilst allowing specific housing needs and typologies to vary by location. Long-term retention of value would be baked in from the start, with land or monetary contributions held in perpetuity through registered community housing providers, registered charities, or iwi and Māori providers with communal interests and long-term asset-holding capacity.

Seizing the moment: RMA reform opportunity

The current reform of the Resource Management Act presents what he sees as the ideal window for embedding Inclusionary Housing into New Zealand's planning system. Waiting to add it later would make getting the nuances right much harder.

The new legislation will require a massive undertaking by local authorities to zone land for 30 years and provide infrastructure. Embedding Inclusionary Housing from the beginning would capture value uplift that would otherwise create windfall gains, moderating the kind of shock Auckland experienced with the Unitary Plan. When inclusionary requirements are known upfront, developers factor them into negotiations with landowners from the very beginning. Introducing requirements later forces a phased-in approach and creates much greater friction. Timing matters enormously.

Addressing developer concerns

The development community's resistance to Inclusionary Housing, he argues, stems largely from uncertainty rather than fundamental opposition. Everyone recognises the need for thriving, affordable communities. The friction arises around implementation.

His experience in California's Central Valley offers an instructive model. In the early 2000s, as more local authorities considered inclusionary policies, the Bay Area Association of Home Builders proactively reached out to Chris and colleagues. Rather than waiting for government mandates, they negotiated principles for how Inclusionary Housing could work across multiple jurisdictions.

He notes "That was a proactive approach, recognising that the workers that they needed were often driving for an hour and a half, two hours from the Central Valley," he recalls. The resulting frameworks provided simplicity, replicability, and crucially, certainty.

He points out "Developers are private businesses. They're organised to build homes to make money to employ people. So it needs to work."

The fiscal reality

In New Zealand's current fiscally constrained environment, no government appears capable of tackling the housing affordability crisis through direct funding alone. Estimates of what's needed range from $5 billion to $20 billion, sums universally acknowledged as unavailable in the near term.

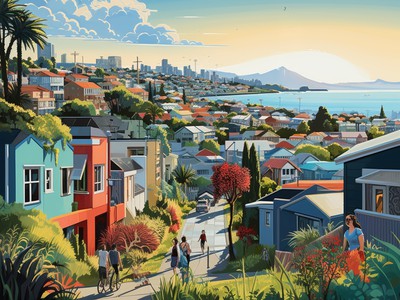

Inclusionary Housing represents an additional tool alongside the certainty and speed improvements promised by RMA reform. It's particularly valuable in housing markets like Wellington, where multiple territorial authorities function within one employment market, with workers commuting between Kāpiti Coast, the Hutt Valley, and Wellington City.

He explains "It really needs to be applied across that market area and you can't have every local authority having to figure it out on their own." National frameworks with market-area-specific requirements offer the most practical path forward.

Building balanced communities

Beyond the technical and fiscal arguments, Chris returns repeatedly to Inclusionary Housing's fundamental purpose: ensuring all people are well-housed within communities. When land is provided in new growth areas under inclusionary requirements, those areas serve everyone, not just certain income bands.

The typical pattern, developments dominated by three-, four-, and five-bedroom homes, creates predictable problems. Young families move in, children grow up and move away, parents reach retirement wanting to stay near their church and rugby club but finding no suitable housing. They're tired of maintaining large sections but see nothing that meets their changing needs.

He notes "Through Inclusionary Housing you can bake those in from the beginning so that you end up with a mix of typologies right at the beginning and that community is able to grow and age and still move around."

Chris is particularly passionate about accessibility for people with disabilities. New Zealand lags badly behind other developed nations in residential accessibility requirements, with hundreds of young people with disabilities now living in aged care facilities simply because adequate housing doesn't exist. Updated housing needs analyses, tied to planning reviews and broken down by age, household composition, disability status, and ethnicity, would reveal exactly what's needed.

"We know that Māori and Pacific and elderly and youth and disabled people are not well-served in most of our communities," he states plainly. "If we're able to drill down and understand the size and the quantum of that, then we'd have a clear plan."

Beyond the market

For those who believe unfettered markets will eventually deliver housing affordability, he points to 35 years of evidence suggesting otherwise. Every region in New Zealand is classified as either severely or highly unaffordable, with median income to housing cost ratios between six and twelve when international norms suggest three to three-and-a-half.

This isn't solely about developer greed. Tax policy favouring landlords over owner-occupiers, historical investment shocks, and capital flowing into property trading rather than productive businesses, all play roles. Until New Zealanders invest in innovative companies rather than trading houses with each other, productivity will remain constrained. He states "We're not going to lift productivity as long as we pour the bulk of our savings into trading houses with each other rather than investing in businesses."

The market has a critical role, but it will always struggle to serve those on lowest incomes. That's where the mix matters: government support for those needing ongoing assistance, Inclusionary Housing and community providers for the middle band, and markets addressing the rest. Even Auckland's massive density uplift only changed the rate of increase, it didn't reverse it. Truly addressing affordability requires incomes growing faster than housing costs over sustained periods.

The case for acting now

After a decade of Community Housing Aotearoa pushing for Inclusionary Housing, Chris finds the repeated refrain, "not the right time", increasingly hollow. With legislative reform underway and housing unaffordability affecting growing numbers of elderly, disabled, and low-to-moderate- income New Zealanders, when exactly is the right time?

"We've had the experience in Queenstown. It's worked. It hasn't tanked the market," he points out. "We have the examples internationally of where it's worked. So we're not starting from zero." "No one over the last 10 years has identified a different option to address our needs. If we don't have anything else to hand, why aren't we using the tool that's there in front of us?"

The elegance of the solution appeals to something fundamentally communal: capturing a portion of value uplift that landowners didn't create themselves and setting it aside forever for affordable housing. It's number-eight-wire ingenuity applied to policy, taking what works, adapting it to local conditions, and having a genuine crack at solving a problem that affects hundreds of thousands of New Zealanders.

The opportunity sits before the country. The question is whether there's sufficient will to seize it.