Dr Michael Rehm's work on Inclusionary Housing in New Zealand reveals a stark reality: if the country had implemented Inclusionary Housing nationally in 2016, approximately 20,000 perpetually affordable homes would now exist in the housing system.

This figure, equivalent to the current social housing wait list, represents not just a missed opportunity but a continuing failure to address New Zealand's housing affordability crisis through proven international mechanisms.

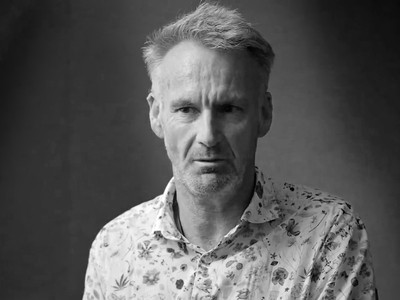

As a property academic at the University of Auckland Business School with over 20 years of experience researching New Zealand's housing market, Michael was directly engaged by Auckland Council during the formation of the city's unitary plan to conduct feasibility studies and analyse proposed Inclusionary Zoning provisions. His extensive consultation with developers, planners, and market stakeholders provided deep insights into both the technical mechanics of Inclusionary Housing and the political challenges of implementing market interventions in New Zealand's predominantly market-driven system.

Understanding Inclusionary Housing as a planning tool

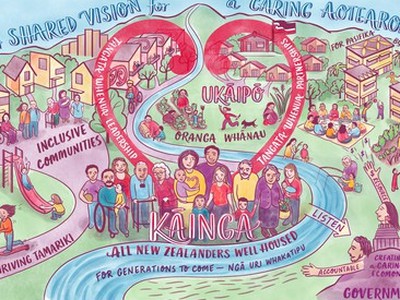

Inclusionary Housing, also known as Inclusionary Zoning, represents a planning tool designed to address market failure in housing provision. He describes it as a market intervention that becomes necessary when the housing system fails to produce affordable homes across the economic spectrum. The approach typically requires or incentivises developers to set aside a proportion of approved housing to be offered at reduced price points, enabling people who cannot otherwise afford market-rate housing to access stable accommodation.

In the Auckland Council context, his research focused particularly on the intermediate market — often called 'key workers.' These individuals include first responders, teachers, nurses, and other essential community workers whose salaries, while adequate in previous generations for homeownership, no longer provide access to the property market given current affordability constraints. This intermediate segment sits between those eligible for social housing and those who can comfortably afford market-rate purchases or rentals, representing a growing cohort of economically stressed households.

The fundamental premise behind Inclusionary Housing acknowledges that in a properly functioning market, such interventions would be unnecessary. However, across all political perspectives in New Zealand, there exists broad recognition of market failure in housing provision. When markets fail to produce housing for people across the economic spectrum, policy interventions become not just justified but necessary to prevent social and economic dysfunction.

The Auckland experiment: lessons learnt

Auckland's attempt to implement Inclusionary Zoning approximately a decade ago collapsed due to several critical design flaws and stakeholder absences. Michael identifies the most significant failure as the lack of involvement from community housing providers during the policy development phase. Without these long-term stewards at the table, the scheme lacked institutional mechanisms to ensure affordable units remained accessible to eligible households over time rather than becoming windfall gains for initially fortunate purchasers.

The developer community, with whom he conducted extensive consultations, expressed strong opposition to the concept. Their objections fell into two primary categories. First, high-end developers particularly disliked having price-controlled products within their developments, perceiving this as a reduction in overall project value. Second, many developers viewed the policy as arbitrarily conferring windfall gains on certain lucky individuals without addressing underlying housing supply issues.

He acknowledges empathising with some of these concerns, noting that they highlight genuine design challenges that must be addressed for Inclusionary Housing to succeed. The absence of transparency requirements, clear eligibility criteria, and mechanisms to maintain perpetual affordability created loopholes that developers exploited, ultimately causing the initiative's collapse. Without community housing providers managing the affordable units and ensuring they remained accessible to eligible households across generations, the scheme simply transferred wealth to initial purchasers rather than creating lasting affordable housing stock.

The essential central role of CHPs in Inclusionary Housing

Drawing from Auckland's failed experiment and international best practices, he outlines several critical design elements necessary for successful Inclusionary Housing implementation in New Zealand. Transparency stands paramount.

All parties must understand how the system operates, who qualifies, and how affordability is maintained over time.

The involvement of community housing providers emerges as the cornerstone of any viable Inclusionary Housing scheme. These organisations serve as long-term stewards, managing affordable units to ensure they remain accessible to eligible households rather than becoming one-time windfalls. He describes CHPs as essential 'central players' that provide the staying power developers inherently lack: "Developers come in, they're going to build this, they're going to sell it, and they don't want to know. Often it's Phoenix-type companies that are born for this project and die at the end of the project."

Without CHPs serving as institutional anchors, Auckland's earlier Inclusionary Housing attempt collapsed into exactly what critics predicted — a system conferring windfall gains on fortunate individuals without creating lasting affordable housing stock. This stewardship role extends far beyond simple property management. CHPs monitor occupancy to prevent abuse such as purchasing affordable units only to rent them out for profit, verify ongoing eligibility to ensure homes serve their intended recipients, and manage resales to maintain affordability across generations.

The regulatory framework surrounding CHPs proves crucial to their effectiveness. As registered entities overseen by the Community Housing Regulatory Authority, and for full members of Community Housing Aotearoa, additionally regulated as charities by the Department of Internal Affairs, these organisations operate under rigorous accountability measures. This oversight addresses the scepticism he encountered during his developer consultations: "You could feel the scepticism of how the various ways that it could be abused on all sides." he notes. CHPs' regulatory status provides assurance to developers, government, and the public that the system operates fairly, transparently, and for genuine public benefit rather than private exploitation.

Developer incentives represent another crucial component. Rather than purely mandate-based approaches that developers perceive as punitive, Michael advocates for mechanisms like development contribution offsets. Under such arrangements, developers who include affordable housing could receive reductions in other regulatory costs, creating a carrot-and-stick approach that encourages participation while maintaining housing supply. He frames this as an 'academic trick' — raising overall development contributions whilst reducing them for compliant developers, creating perceived benefit without actual cost to council.

The question of perpetual affordability requires careful consideration. While ensuring affordable units remain accessible across generations prevents individual windfall gains, some flexibility might be appropriate. He suggests considering time-limited affordability periods that allow occupants to eventually purchase at market rates, potentially treating the affordable housing as a stepping stone toward full market participation rather than permanent below-market accommodation. This approach recognises that the intermediate market differs fundamentally from social housing, potentially justifying different long-term approaches. However, any such flexibility must be managed by CHPs to ensure it serves policy objectives rather than undermining them —maintaining the crucial distinction between a genuine hand-up for key workers and a windfall gain for lucky individuals.

The 20,000 home calculation and its implications

His calculation that New Zealand would now have approximately 20,000 perpetually affordable homes had Inclusionary Zoning been implemented nationally in 2016 derives from applying typical Inclusionary Housing percentages to the volume of new housing construction over recent years. Assuming a five to ten percent set-aside requirement across new developments, the cumulative effect over nearly a decade would have produced this substantial portfolio.

The significance of this figure extends beyond its absolute size. These 20,000 homes would represent stock that continues growing year after year, with each subsequent year's construction adding to the perpetually affordable inventory. In Auckland alone, where the intermediate housing market comprises approximately 100,000 households, these 20,000 homes would represent a fifth of current need — a substantial foundation that would continue expanding.

The comparison to the current social housing waitlist proves particularly striking. Rather than a completely separate policy challenge requiring government acquisition or construction of social housing, a parallel stock of intermediate affordable housing would exist, serving a different but equally important cohort of housing-stressed New Zealanders. This demonstrates how Inclusionary Housing complements rather than replaces traditional social housing provision, addressing the continuum of housing need across different income levels.

Value capture and development context

The conversation extends to broader questions of value capture. He uses Auckland's City Rail Link as an illustrative case, where billions of dollars in public infrastructure investment generate substantial private property value uplifts for landowners near new stations without any investment on their part. The question becomes whether and how to capture some portion of this publicly-created value for community benefit, potentially through affordable housing requirements.

However, he expresses caution about targeted value capture mechanisms that single out specific beneficiaries of infrastructure investment. Developers and landowners near transit stations perceive their capital gains as earned through strategic positioning rather than windfall gains from public investment. Attempting to capture these gains directly would generate immediate political resistance and potentially undermine developer cooperation with affordable housing initiatives.

Instead, Michael advocates for broader application. If Inclusionary Housing requirements apply universally across Auckland developments at five percent, for example, rather than targeting specific locations, the approach becomes more palatable. This broad application avoids accusations of unfair targeting while still achieving the policy objective of creating affordable housing supply.

For genuine windfall gains from infrastructure investment, he suggests targeted rates might prove more effective than development-phase value capture. Property owners near new transit stations benefit from amenity improvements they did not create; recognising this through rating systems that charge for location-based benefits might generate less resistance than attempting to capture value during the development approval process.

Land banking and supply considerations

The discussion necessarily addresses the critical concern that any developer-focused regulation might reduce housing supply — potentially achieving affordable housing percentages of a much smaller total development volume. This concern represents the developer community's strongest argument against and requires serious consideration.

He suggests that well-designed Inclusionary Housing schemes with developer-friendly incentives need not reduce supply. The key lies in ensuring participation remains attractive through mechanisms like development contribution offsets, streamlined approval processes for compliant developments, or other regulatory relief that balances the affordable housing requirement.

Regarding land banking — where landowners on urban fringes hold undeveloped land awaiting value appreciation — he sees this as potentially a more appropriate target for value capture mechanisms than Inclusionary Housing. Targeted rates on underutilised land that could support housing development but remains intentionally undeveloped might encourage more active land use while generating revenue that could support affordable housing initiatives.

Political feasibility and stakeholder alignment

Despite the Auckland failure, Michael maintains optimism about Inclusionary Housing's political viability in New Zealand. He observes that both sides of the political spectrum should find elements of the approach appealing — it leverages market activity to create affordable housing without requiring direct government expenditure, while addressing a market failure that all parties acknowledge.

The challenge lies in bringing all necessary stakeholders to the table from the policy design phase. Community housing providers must participate as core partners rather than afterthoughts. The development community, while initially resistant, provided valuable insights during his research when engaged respectfully and genuinely. He emphasises that developers were generally open and collaborative during consultation, even if they opposed the concept, and that their technical expertise proves essential for workable policy design.

Government officials must provide clear signals about housing crisis recognition and willingness to pursue solutions, creating space for market interventions that would otherwise face resistance. This requires acknowledging that purely market-based approaches have failed to deliver housing across the economic spectrum and that policy tools like Inclusionary Housing represent necessary corrections rather than ideological impositions.

From missed opportunity to future action

The story of Inclusionary Housing in New Zealand represents a significant missed opportunity. The 20,000 perpetually affordable homes that would now exist had different decisions been made in 2016 would represent not just shelter for families but a growing asset base serving intermediate market households across generations. Each year would add to this stock, progressively addressing the affordability crisis facing essential workers and other moderate-income households.

Michael's analysis demonstrates that technical solutions exist for the design challenges that undermined Auckland's earlier attempt. Transparency requirements, community housing provider involvement, developer incentives, and clear perpetual affordability mechanisms can create workable schemes that serve multiple objectives simultaneously. The question remains whether New Zealand's policy environment will support such interventions or whether another decade will pass before the country adopts approaches that prove effective internationally.

For the growing number of New Zealanders experiencing housing stress — the 180,000 households nationally paying well over 30 percent of income on housing costs — the missed opportunity of Inclusionary Housing represents more than policy failure. It represents years of financial strain, reduced life opportunities, and diminished wellbeing that alternative policy choices might have prevented. The pathway forward requires placing community housing providers at the centre of any future Inclusionary Housing scheme. Their unique position commanding cross-party political respect, combined with their regulatory oversight and proven stewardship capabilities, makes them indispensable to transforming policy intent into lasting affordable housing stock. Without CHPs serving as institutional anchors, any new attempt risks repeating Auckland's failure.

Whether future governments will learn from Auckland's failure and implement the essential design improvements, Michael acknowledges, remains an open question, but the cost of continued inaction becomes clearer with each passing year.