[00:00:04]

Clare, thanks so much for taking time to meet with us. It's great to be here in London and getting an international perspective on inclusionary zoning, inclusionary housing. Clare, could you tell us a little bit about the organisation you work for and your role within it?

[00:00:18]

I've been practising for about 25 years, a little bit longer, and I trained originally as a town planner. Very quickly realised that there were bigger issues that we were facing and focused on housing and housing delivery.

[00:00:37]

As part of that, in the UK, very early in my career, viability started to be raised as to... Can schemes afford to deliver affordable housing? How much can they afford to deliver, et cetera? So I've made a career out of affordable housing and negotiating affordable housing on behalf of developers for some of the biggest schemes in the UK, say Battersea Power Station, Ells Court, King's Cross, the Olympics.

[00:01:05]

I work on Wembley, Tottenham, anything big is my bag. But in addition to that, we do lots of other stuff with RPs, funding, trying to get really complex schemes up and running, being able to find shared outcomes to be able to unlock development.

[00:01:29]

And that's all over the country. So I work for Cambridge University, Oxford University, Imperial, the Wellcome Trust. where we've got a lot of issues with jobs and homes, and it's really about trying to unlock growth. So we set Quad Up 15 years ago, and within that I lead the development economics team. We've also got planning, environmental impact and socioeconomics. And we started up with six of us. There's now about 180 across two offices in London and Leeds. And the scale of the growth, I think, is testament to the fact that in the UK planning is a critical issue. It's a gateway to enabling development, to unlocking growth.

[00:02:14]

And we're working on some of the largest infrastructure projects, so Heathrow, nuclear power stations, ports. We're working on outdoor shopping centres and solar farms and all different types of things. But my focus is housing.

[00:02:30]

Claire, let's talk about housing affordability. In our last edition of the Insight Report, we published some data on the amounts of social and affordable housing in different regions, different countries.

[00:02:43]

The OECD average is one reference point. In New Zealand we're sitting around about 4%. Spain, an outlier, at the bottom of the table at around 1%. The Nordic countries, not surprisingly, are around about the 30 % adhere in the UK or somewhere around 16%, perhaps up to 20%. Where do you see the definition of affordable housing? What does that mean for you here in the British context? Yeah. So in the UK it's become quite an established formula. So it's a percentage of income.

[00:03:20]

What's the housing cost as a percentage of your gross income? affordability for us, there's two ways. You can look at it sort of a more sub -regional city way, where you look at what's the cost of a house and what's that multiple of the average income. But really, we tend to get a lot more focused because that masks so much because you don't have a linear relationship and you don't know where the highs and lows are when you look at those average incomes. Even if you look at low quarter, there's a huge spread in terms of low quarter.

[00:03:54]

So generally, our policy controls and our policy tests here are based on a proportion of your gross or net income that's able to be spent on housing costs. And your housing costs should also include generally your service charge. So we would be working on sort of a third of your income, no more than a third of your income. Household income should be being spent on your housing costs. And what we see in the UK is that most of our Section 106 agreements, so they're the legal agreements that go with developer schemes that are then required to deliver affordable housing, have that formula linked in.

[00:04:32]

So to be able to ensure something is affordable, then the cost of the rent or the cost of the mortgage plus the rent, if it's an intermediate product, isn't able to be more than the percentage that's specified in terms of income. And that's quite controversial in some respects. It's a very binary assessment and it doesn't take into account... different household circumstances.

[00:04:58]

So you could have two nurses living together and their choice is to spend 45 % of their household income very close to the hospital, means that they have zero travel time, gives them a much better quality of life for shift work, etc. But in affordability terms, they would be saying, no, you're spending too much of your income. And the only alternative they may have is to move half an hour or plus away.

[00:05:27]

And then they've got, okay, they can spend 40 % of their income, but then they've got to pay for travel. They've got all of the other issues associated with, you know, out of hours working, etc., being able to get to where they live. So our assessment of affordability is helpful because it means people aren't spending too much of their money on their housing costs, but it does need to be looked at with a little bit more flexibility, maybe.

[00:05:54]

Look, we're going to get a little bit technical and into planning instruments now. So section 106, could you tell us about the transition from section 106 to the community infrastructure levy and any lessons that have been learned along the way? We started off with a situation where we had the private sector principally delivering market housing and the public sector principally delivering affordable housing, you know, in the 60s. And where that's changed is that central government said, actually, we don't want to be so involved in delivery of housing. So we're going to encourage the setting up of RSLs and RPs.

[00:06:33]

So they're quasi -autonomous. non -governmental organisations, which are effectively charities, so registered providers as an RP, registered social landlord as an RSL, their sort of charity status, their sole purpose is to deliver affordable housing. So they ended up taking over some of the existing council's housing, so there would be transfers into the RPs who would then operate affordable housing.

[00:07:00]

And then they also started to be able to benefit from government grant funding, and their purpose was to be able to deliver more affordable homes. So we went from having local authority delivered housing, centrally government -backed delivered housing, to registered providers. That worked quite well for a while, but we weren't delivering enough homes whatsoever. The UK isn't delivering enough homes overall, let alone affordable homes. And so as we went through increasing funding reductions, so grant became harder and harder to get, those RPs started to struggle more in terms of how they could make the maths work. They were facing quite a lot of challenges in terms of the stock that they were trying to operate and

[00:07:50]

the cost of the refurb and maintaining that stock, et cetera. So investing in new affordable housing was only a small bit of what they were doing in addition to their wider day job. So the government here started to want to look to have mixed and balanced communities. So they started to look to new developments who bring in affordable housing that the RPs could then purchase and they would then deliver and bring them forwards.

[00:08:18]

And that system very quickly evolved from being one where developers were effectively giving a little bit of land to one where developers were building a lot of the homes and then selling them to an RP but for a very, very low price. So the RP will capitalise the rental income that they can get from the regulated rents set by central government and they will say we can afford £140 a square foot. And then the developer is turning around saying, well, I'm going to buy the land, build the housing, go through all of the processes associated with that, take all of the construction risk.

[00:08:59]

I'm going to create a completed product and I'm then going to sell that when it's constructed to an RP and transfer that over. So they may be, their cost may be £350, £400 a square foot all in and then they're selling it at a loss because they're then selling it to the RP at £140 a square foot. And this system slowly came in initially and then very quickly got a lot of pace behind it. So it was the PPG3 that then evolved into what now the NPPG, etc.

[00:09:36]

And in policy now, nationally in the UK, we are told every council needs to have a development plan that requires a proportion of affordable housing on most sites. If it's a very small site, 15 units or less, then there can be provisions not to, but any large site needs to be delivering affordable housing. And that significant onus now falls on the And because in a lot of situations, the policy ask is being set quite high, so it's not uncommon to be 30%, 35 % in London. It's 50 % of the homes that you're delivering have to be affordable.

[00:10:20]

Developers are saying, I can't afford to do that. math. The math doesn't work. I can't afford to buy, build, take market risk, fund and provide half of those as affordable homes or I'm effectively making a loss.

[00:10:36]

So we then had since early 2000s, maybe 2010, a massive growth in the viability assessment element of policy, which is where we turn around and say, as a developer, we can't afford to deliver the policy that you're asking for. Here's our viability. Have a look at it. And initially that worked quite well, but then there was a realization that land was distorting the outcome and so developers were going and spending a lot of money on land. They were buying land at full market price and they were getting into competition with each other and paying more and more and more for land. They were then turning around putting that land purchase price

[00:11:23]

into an appraisal and saying, I can't afford to be able to buy it, to build the affordable housing. So where we've now evolved to is to make sure we have land value capture, is we now have a lot of policy controls.

[00:11:37]

You can pay more for land, that's up to you, but when you come to us and put together a financial appraisal that says you can't afford to deliver our ask in terms of affordable housing, you can only allow existing use value plus a little bit of profit. as part of that assessment. So you may be wanting to pay three times the actual land value, but we will only allow you to pay the existing use value plus say 20 or 30 percent. So that control that's being brought in has been intended to make sure that the biggest chunk of land value capture goes straight back into policy and delivering more benefits for the largest policy ask in England so that

[00:12:26]

that money gets captured for affordable housing and isn't lost through being given to land owners as part of the transaction process. Thank you, very interesting. We in New Zealand, in a New Zealand context, have experimented in various regions with inclusionary zoning and value capture, but it's been sporadic and open to legal challenge.

[00:12:52]

Interested to hear your views on the importance of centrally legislated or clear national planning rules, and what that looks like when you've applied that in the UK from a legal perspective, because we've seen legal challenges in New Zealand and in regions where we have tried to apply inclusionary zoning and it's become problematic for our providers in the New Zealand context.

[00:13:16]

Absolutely critical. Housing has to be viewed, particularly affordable housing, alongside other types of housing.

[00:13:24]

It has to be viewed as infrastructure. and it can't be party political.

[00:13:32]

There needs to be a centralised national view about some key principles associated with positively planning pipeline of housing for areas. And as part of that, it's really important that those homes meet needs.

[00:13:51]

And assessment of need doesn't need to be overly onerous, but it needs to consider the wider objectives for an area. So if your area is limited in terms of heritage, then you would be wanting to make sure something's lower density. If your area is next to a university, you may be wanting to be able, or a hospital, you may be wanting to try and encourage smaller homes that really support the types of workers that are going to be wanting to work in that location to create sustainable. settlements, et cetera, around these key employers.

[00:14:31]

And where we're really great is our national policy is brilliant. Our national policy sets out housing is our number one policy objective. We should be doing everything we possibly can to deliver a mix of housing for a mix of different types of people in a mix of different typologies. And that's said to be for sale, for rent, for older, for younger, for first time buyers, all different types of homes. And as part of that an element should be affordable housing if there is an identified need.

[00:15:02]

It then sort of stops and says now every local authority, you now need to come up with your own approach to doing that. And that's where the wheels fall off a because every authority wants as much affordable housing as possible and they ask a lot and then they ask for a lot of other things alongside that. They want affordable workspace, they want social infrastructure, so schools, doctors surgeries, they want open space, great things for a great place, great community, but then they also ask for affordable housing at very very high So that tension at the local level is where what we're finding is we've had a transition and really good examples London where we

[00:15:49]

had Ken Livingstone brought in in the first London plan, a very high level affordable housing policy, it was probably five lines. We've now got an affordable housing policy in the current London plan that's probably covers 20 pages and there's sub policy after sub policy after sub policy and we've gone from a situation where we were delivering lots of homes overall and as part of that a good proportion of affordable homes, so maybe 20%, to a situation under Boris where we were delivering loads of homes overall and a good proportion of affordable housing that in housing numbers was higher than Cairns, even though percentages may not have looked quite as high, to a situation where now

[00:16:38]

policy is so onerous, it's so hard and the ask, the square is impossible, the circle is impossible to square, the square is impossible to circle, but it's absolutely impossible for anyone to be able to get to the bottom of it and now we're in a situation where our overall delivery has fallen. flat on the floor, we're not delivering anything because policy is now counterproductive to why it's there.

[00:17:04]

So I'm hearing you say yes to those planning instruments being in place and also there's some nuance there in the sense that being a bit less rigid about how they're applied in the marketplace is very helpful. You and your company have delivered huge amounts of affordable housing in the UTA context. So what lessons have you learned? What things are working well that you'd like to see more of more often and in more places and what are the pathways that you think are going to work best to get that moving?

[00:17:34]

So I think the overall context is great in terms of that national policy. I would then be saying through that national policy, what's your business plan for your area in terms of housing? What are the outcomes you're trying to achieve? What do you think your growth is in terms of the number of homes that you're going to need and what types of homes do you think you're going to need to be able to see your place, to see a community, see a town, see a city because at all different levels, be able to achieve its best possible outcomes overall in terms of schools, jobs, education, health, wellbeing.

[00:18:12]

What are the things that you need to get to over 15 years? And now let's break that into what does that mean in terms of the types of home housing, the scale of housing, the housing numbers that you need. So these are our outcomes that we're trying to achieve across a community.

[00:18:29]

What's our best way to get there? And let's put the policies in place that incentivise, that act as a carrot, not a stick. to bring developers and the public sector and the community housing providers together along with the communities to say, do you know what, affordable housing is great over here. Market housing works really well there. That's a really high value location.

[00:18:57]

So actually we're much better. The opportunity cost of delivering affordable housing on that site means it's going to cost three times the amount of delivering it on that site. So we're much better in that situation, taking a financial contribution, putting that into a pot and using that on these three locations and delivering three for the price of one than forcing that developer who can actually make a really great scheme over there that works really well with the adjacent commercial, et cetera.

[00:19:27]

So to have those flexibilities to allow school. outcomes to be achieved, negotiation, and the more you get, the more you get. That two -way, we're in this together to create the best possible outcomes for our communities.

[00:19:46]

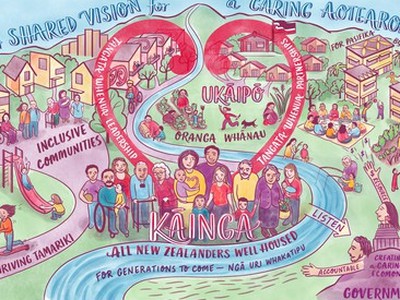

That's the policy framework that I see as being really effective. So what I'm hearing you talk about there resonates for us in terms of a place -based approach and we've just come from filming in the Waikato, which is a region in New Zealand where there is a Waikato housing initiative which brings together a broad range of key stakeholders, local government, mana whenua, Māori, community providers, central government all together to deliver a long -term set of plans and objectives 25 years, 50 years into the future.

[00:20:19]

Wonderful. Exactly what we need. And we've done it here in like small little nuggets where you see what can be achieved if you just have that. You go in and you say to a council as a developer, can you give us the gift of negotiation? Can we please just engage? We understand your policy. We understand what your policy is trying to achieve. We think we can achieve that in a bigger, better way. So please, can we just have a conversation?

[00:20:48]

And when you get the hearts and minds together, the outcomes are brilliant. So the Shell Centre is a really good example, which is in the Borough of Lambeth and it's a very high density site between Waterloo station and the river. Very, very complex to build on because of underground, railway, et cetera. And buildings are, it's now built, dense.

[00:21:16]

So it's, it's very much urban living. And then you look at the affordable housing needs of land birth. They are for families, they're for people who need access to open space, schools who want to be part of a less dense community, generally. So the negotiation there saw the developer, Canary Wharf Group and Qatari DR, identify sites in proximity.

[00:21:45]

And we found a site called Lollard Street, which was counselling land. And after a process, we were able to enter into a licence to build on the counselling land. And instead of providing the affordable housing, we provided some on site. most of it was in this Lollard Street. We were able to knock down a car park, which had a great nursery on top of it, but that was really struggling to operate and had lots of operational problems and you had to go up a massive ramp to get to it. Took that down to ground.

[00:22:23]

We built a new block and then townhouses all the way along the front and then that all faced onto a park. That scheme delivered three to one, so we've got three times the number of homes by using the money that would have been on site to deliver in that way. And the outcomes were so much better in terms of meeting the council's needs and then that then stayed with the council. Those properties are now owned. by the council, by Lambert, and are being occupied by families on the housing waiting list.

[00:22:59]

And my experience generally is that where you take that community -based approach, the outcomes are so much better rather than forcing a developer to try and incorporate housing, three floors affordable, three floors market, trying to force those outcomes,

[00:23:26]

you actually get much, much better outcomes by working with the communities themselves. And that doesn't mean not mixed and balanced. We've got ourselves into a bit of a pickle in the UK as well, through our poor doors discussions, where If we don't have mixed blocks, sometimes that's for you, just not mixed and balanced communities.

[00:23:48]

And that then in turn is reducing the amount of affordable housing that we can actually contribute because it's really an efficient A to build, but also for the operator to manage. So by just taking a more community based approach, what feels right to the people that are going to live there and let them be part of that overall delivery. Claire, we've got a working example in the Queenstown Lakes District of New Zealand where there is a percentage, in their case typically what it's been is around 5 % of any new development is transferred either as money or as developed sections and transferred through to the Community Housing Trust, which effectively operates as a community land trust. The objective there is to retain that affordable housing

[00:24:36]

and recycle it in perpetuity.

[00:24:40]

Is that sort of a mechanism working in the UK?

[00:24:43]

Yeah, so we do. We have community land trusts that are very similar to what you are describing.

[00:24:49]

They aren't as frequent. That's not the common way of what we do. Instead, what tends to happen is, the description I made earlier, the RP, the registered provider, either delivers and operates, in which case they keep those affordable homes in perpetuity. They will be either for rent or they'll be what we call intermediate tenure, which is either a discount market rent or a discount market sale. And within the discount market sale, there's different products, some where you rent and buy, some where you buy a percentage of the open market value, and they're all held in perpetuity. And then the other element is the developer delivered affordable housing. Now that comes with a huge number of controls.

[00:25:31]

So that will be regulated through a Section 106 agreement, which is the legal agreement that goes with the planning permission. That then requires that developer to build the affordable homes themselves in accordance with a certain programme. They can't release the market housing until they've made specific progress with the affordable housing. That affordable housing then gets transferred generally to a registered provider, but it comes with a huge number of controls. So those controls will be about the tenure, the pricing, how the rent's set, how that rent increases, or if it's to be sold, the basis on which it's to be sold, what percentage of equity.

[00:26:10]

It will set out who will be the priority as to who will live in there. It will set out affordability controls, so someone can't spend more than X amount of their income. It might set out what job roles they need to be in, so they have to be a key worker. So if they're no longer a key worker, they can't continue to live there. It may have some means testing. It will then have provisions about right to acquire. It will set out indexation of those rents. It is massively onerous and it will also put up so it should be in perpetuity.

[00:26:46]

That has become a huge negotiation and just needs to be really, really simplified so that everyone's clear as to what the ask is. So that definitely isn't the model where it's say belt and braces that there isn't that flex. Whereas when you can sit it with an organisation that you've got real faith in that's got terms of reference that are we will keep these homes for as long as possible as affordable housing and we will make sure they're prioritised people in housing need and that's their Interesting that you mention mixed tenure. What's your view on how that works effectively in terms of mixing different tenures, different ages, different people within a

[00:27:35]

single community? I think if you walk around London, you'll walk past a block and you'll say, oh that's perhaps owned by the council. You will then look on the other side of the street and there might be some beautiful townhouses. So we immediately, based on our heritage, see those differentials and I don't get upset by that.

[00:28:02]

What I think is really important is that those homes are really good quality homes and that they are well mixed. overall, they all have the same access to community facilities. They have access to really good lighting and are secured by design. And they have really good internal lighting and really good space standards. And so I think if we start to focus on the perception of the person walking down the street, rather than the perception of the person that's living in the home, then things start to fall apart because we start to overthink the principle, whereas the priority should be to deliver as many homes overall and as meaningful a proportion of affordable homes as part of that.

[00:28:49]

And you can easily have provisions whereby if it's 500 units, you say, well, we want to see this the 10 % affordable housing delivered across three different areas and we want that to be well distributed. That's the point of principle. What I don't think is the best outcome is to say, for every 10 homes, we want to see one that's affordable and that to be distributed evenly across a whole area, generally, because that leads to really challenging management and operational issues, which adds to costs.

[00:29:25]

And the more you add to costs, the harder it is to deliver more affordable homes. So I think we need to be careful about using

[00:29:34]

points of hypothetical principle to define the outcome and instead make sure we're delivering a mix of tenures, a mix of types, a mix of sizes, a mix of styles of housing to meet different needs, families, older people, single people, etc. rather than being quite so worried about which is private tenure, which is affordable tenure.

[00:30:03]

And my experience on a lot of the schemes that we deliver is that A, developers are very happy for the affordable housing to come forward alongside the market housing because it helps with cash flow, it helps in terms of absorption rates. So there's no issue.

[00:30:23]

Where there is a challenge is where they're being required by the registered provider that's going to take those homes on to try and make sure they've got specific management. operational requirements that enable them to manage those properties really effectively that doesn't work with market housing. And that's really, really difficult. And it's the RPs just as much as the private developers that are saying, let's integrate, but that doesn't need to be within a single building.

[00:30:53]

So I think you can deal with a lot of those challenges through good quality design and placemaking, rather than through the concept of if you have two different blocks, that's rich and poor.

[00:31:06]

And I just think we can be a lot more progressive than that backwards. I feel that's quite a backwards thinking and it's very much very pessimistic. So to me, the outcome would be, developer, you're going to build some affordable homes, you're going to make provision, show us how you're going to achieve our aspiration that they should be mixed and balanced communities. Come up with some really great ideas, rather than saying every scheme that comes forward needs to have. pepper -potted, affordable and market housing, and that then being a fix. And, you know, good places that live well are designed in a way that are integrated really effectively. Look at our cities, they haven't been designed using those sorts of principles.

[00:31:53]

They've organically grown and people live together really effectively. So capture that energy.

[00:32:00]

Thank you, Claire. Have you got any other thoughts on what we've covered so far? I would say look to the market to help you. So the market can actually deliver really effective. entry level housing.

[00:32:20]

So your challenge with affordable housing is that there's always a gap between market housing, the lowest cost rental housing that governments may be able to support and provide, and then there's this gap in the middle of people who are on the edge. If there was more lower quartile housing, priced housing available, they probably would be able to afford those homes. Or if there was better quality, lower quartile private rental housing, they could afford those homes.

[00:32:51]

Now that's a market where investors are actually really interested and with a little bit of support by central government, see whether they turn around to investors and they say, we will underwrite the rents. or we will give you, you only have to deliver it for 25 years, put some flex in there and then encourage investors to come into that entry level market to try and boost that supply. Because what that will do is bring down your affordability where we started, it will bring down your affordability hurdle rate, it will bring that lower so that the people that you're then having to target for the very traditional affordable housing is much more consolidated. So you're investing your public money and your public support

[00:33:39]

and your community housing work on a smaller focused group and you're then encouraging and working and collaborating with the private sector to then boost that entry level market.

[00:33:54]

And it's very investable. Investors in the UK are super interested in it, institutional investors. Where what they need is central government to work with them to get some clarity around what the terms are They can't be going to every authority Negotiating something it needs to be sort of a government backed approach to say we will really encourage investment in that sector, right? so it's still essential to have a Central government long -term policy alongside place -based approaches to make this work Alongside so it's but I think rather than looking at it as your community traditional affordable housing and market housing Try and create a middle sector So try and

[00:34:40]

bring those two together by joining them and have overlap Between market housing and affordable housing create that new product area, which is actually Overlapping because then you get an opportunity for people in affordable housing to move into that middle space And from that middle space, they can move to private market housing and what your objective should always be is to give people an opportunity to move out of affordable housing and to meet their own housing needs on the open market.

[00:35:12]

So to be able to do that, they need a ladder of opportunities and the private sector can really, really help with that. There's a lot of latent investment potential in that sector. So don't polarise affordable housing into being the two ends. Turn it into a continuum and make it something that's got movement in it, that's agile and where you're not getting the affected bed blockers, where people end up being stuck in affordable housing because there's no better option.

[00:35:45]

Or if they try and move to the private sector, they lose out so much.

[00:35:49]

Incentivise that churn of housing because then you'll get real activity in your housing market, which is exactly what you need. Yeah, yeah, so interesting to hear you use this phrase bed blockers I hadn't heard of that before in in our context our ideal Situation is that when we find a home for somebody that could be their home for life But we find with our policy mechanisms that if their income goes above a certain threshold They have to move on.

[00:36:17]

What's your view on how this could work best? How do we balance the pros and cons of this approach as opposed to here's a house that you can afford to stay in For the rest of your life. I think yeah I think I think there's an extreme of saying your means testing on an annual basis and then kicking people out. That's I Don't agree with that being the approach I do agree that people should be incentivized and encouraged to try and better their housing situation if they're being oversubsidized and they can afford a lot more, and that home could then be being made available for someone else in that community, encouraging someone to make the choice to move within that community, because there's all different types of homes that are then available, just to something with perhaps a little bit less discount. It still might be discounted, but not to the extent

[00:37:06]

they were initially, by incentivising, you're not forcing anyone, but providing those options, rather than just having low cost, high cost, by having steps in between, I think that's really, really important, and the same works in reverse.

[00:37:24]

So, large family homes occupied by two people whose children have left, et cetera, et cetera. Big issue in the UK is that there's nowhere progressive. that those occupiers to move to. So again, you get stalling in the housing market. So what we really, where we see a lot of benefit is in having those wider choices, getting private money in, so it's not costing the public purse, not forcing anyone to do anything, but giving choices to move up through the housing market, to have larger homes, to be able to have more private amenity space, et cetera. And then you get to a point and make sure that the market's then delivering homes you to downsize to, because that again keeps that movement in the housing market and doesn't mean you've got two people living in a

[00:38:14]

family -sized home. And instead you provide other amenities that are really great for them and that work really well. So I think... Don't just think about it as an end state. Think about it as how do you create communities that have choices? Yeah, yeah. Claire, thank you so much for taking time to talk to us today. It's been very informative, particularly around the mechanisms and the flexibility that make these instruments work more effectively.

[00:38:42]

And you know about it. You've done it at scale. We're early in our journey in New Zealand and we're very, very grateful for you sharing your knowledge with us.