Holding Land in Perpetuity for Community Benefit

A key component of an effective Inclusionary Housing programme is ensuring long-term retention of the homes delivered. Various options are used in New Zealand and internationally.

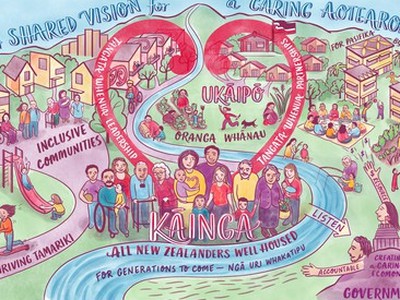

Community Land Trusts (CLTs) manage land and property for community benefits, including affordable housing. They are common in the United Kingdom and the United States.

Their not-for-profit status ensures Inclusionary Housing contributions are maintained for community benefit over time. Sizes range from small organisations with a few homes to larger CLTs with hundreds or thousands of homes and other community facilities.

It is important to consider the geographic area and existing organisations when determining the most appropriate model for holding Inclusionary Housing contributions.

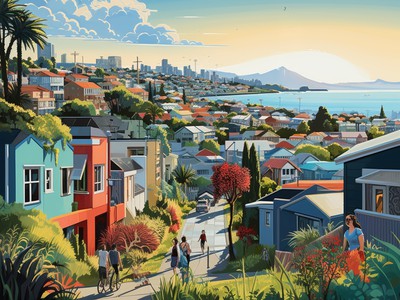

Queenstown Lakes District Council established the Queenstown Lakes Community Housing Trust. The Trust fulfils multiple roles as developer, manager and owner, utilising contributions for long-term community benefits.

The Waikato Community Lands Trust operates over a larger geographic area, receiving property and funds through Waikato councils, donations or Inclusionary Housing. It holds contributions but partners with other organisations to develop and manage housing. Both approaches deliver homes but with different roles.

Other organisations can fulfil retention and stewardship roles, such as Māori entities or local authorities. International and local experience demonstrates there is no single best approach. It should be informed by local conditions and abilities.

The following insights from Thomas Gibbons and May Low of the Waikato Community Lands Trust explore how the Trust began with council support, the practical realities of scaling perpetual affordability models, and why policy levers and genuine sector collaboration are essential for delivering affordable housing to future generations.

Thomas Gibbons: Retaining land affordability across generations

Thomas Gibbons brings law and governance expertise to the Waikato Community Lands Trust's mission of retaining land affordability for future generations. His perspective centres on policy frameworks, funding structures, and the systemic changes needed to deliver housing across the entire continuum.

The Trust's establishment revealed immediate lessons about funding design. Hamilton City Council's initial grant was earmarked solely for land purchase, which on strict reading couldn't extend to even 'putting a spade in the ground.'

Working closely with council, they reshaped the funding arrangement to become fit for purpose, ultimately using it to purchase existing units rather than building new. "We compared that to the cost of establishing new housing and the cost difference was massive," Within the perpetual land ownership framework, the Trust aims to offer diverse products: affordable rentals, leasehold arrangements comparable to Secure Home products, and potentially shared equity models over time. The leasehold model particularly interests Thomas as it could deliver homes at half or less than half the cost of freehold properties. He notes "That's the intention. That's the goal. That there is that massive price difference and one is affordable to people in a way that the other, unfortunately now today, is not."

However, banking policies on leasehold remain a major impediment, but there are initiatives from banks like Westpac and others in NZ which have started to address this. There are also many unresolved issues around large rent reviews that treat residential leases like commercial ones. Thomas calls for central government attention to these barriers, whilst emphasising that leasehold should be one option within a suite of products, not the only choice for younger generations.

His analysis focuses relentlessly on the missing middle — the vast majority of housing delivered by the private market, which produces very few affordable homes. "We spend a lot of time talking about a very small part of the continuum around government community provision," Thomas argues, whilst the large market delivery aspect "really needs more attention from a policy point of view."

Policy levers matter more than funding levers when addressing housing at scale. What kinds of houses can be delivered? What housing is enabled by planning frameworks? What arrangements support up-zoning or Inclusionary Zoning? "Our planning system needs a lot of attention in terms of how and where housing is delivered," he emphasises.

The consequences of inaction extend far beyond housing stress. Home equity traditionally enables business establishment and economic activity. Unaffordable housing increases subsidy costs, drives families toward poverty, and curtails options for people in abusive relationships. "There are all kinds of adverse impacts from housing being unaffordable," he notes, lamenting that increasing house prices are still celebrated as positive outcomes.

He recalls party manifestos from the 1970s that held homeownership for young people as a critical social goal. "We've seemed to have abandoned that idea altogether," he reflects. "It is an indictment on us as a country that we can't think differently about how our housing system works."

Yet Thomas remains hopeful. "We can make different choices. We've done it before." The path forward requires comprehensive system thinking that addresses policy frameworks alongside funding to recognise that the 90% of housing delivered by the market, demands as much attention as the 10% provided through community and government channels.

May Low: Starting small to build perpetual affordability

The Waikato Community Lands Trust began with a straightforward principle: separate the value of land from the value of buildings, then hold that land in perpetuity to provide affordable housing forever. May Low, Co-Chair of the Trust and COO of Kiwi Innovation Network, describes this as the core essence that makes community land trusts work.

Starting with a two million dollar grant from Hamilton City Council, the Trust purchased its first four units on First Street in Hamilton East. Leveraging that initial investment, they doubled their holdings to eight units — two-bedroom homes with garages in a central location near schools, transport, and employment. "We were able to use that as leverage to purchase the other four of that same development," May explains.

The Trust's current model offers affordable rentals targeting households with lower social housing needs who can sustain tenancies when accommodation is genuinely affordable. Partnering with Habitat for Humanity for tenant screening and property management, the Trust ensures residents understand how to care for their homes whilst exploring pathways to progressive home ownership for successful tenants. "If there were people within those units looking to buy, is there an option for us to then say, you've done an amazing job through the rental scheme, why don't we look at a rent to own model?" She suggests.

However, scaling this model faces significant challenges. "Everyone is wanting to almost build empires with land," she observes. Success requires generous donations or, critically, Inclusionary Zoning policies that mandate affordable housing contributions from development.

The Trust actively advocates for such policy changes, pointing to Queenstown Lakes Community Housing Trust as proof that Inclusionary Zoning can work effectively in New Zealand.

May's innovation background shapes her perspective on housing's foundational importance. "When I moved to New Zealand as a young child, having a stable home is actually your basis of building wealth within your family. That's the first rung on the ladder," she reflects. Constant moving due to unaffordable rent fundamentally changes families' lived experiences and prevents putting down roots.

Yet May identifies a deeper barrier: fragmentation within the housing sector itself. "Everyone is trying to empire build themselves," she argues. "The thing that we need to do is put the ego aside and actually work together constructively."

Her vision involves getting everyone around the table speaking the same conversation, moving things forward significantly rather than incrementally at a snail's pace.

Drawing on her commercial expertise, May emphasises an essential principle: "You don't get nothing of a nothing pie. You get something of a bigger pie, but it's better than nothing of a nothing pie." Collaboration creates value that benefits everyone. The alternative is stagnation that helps no one.

The Trust's current eight units represent a starting point. The real potential lies in scaling through Inclusionary Zoning, collaborative funding models, and sector-wide cooperation that prioritises community benefit over individual empire-building.