New Zealand's housing affordability crisis has reached unprecedented levels, with 20,000 families on waiting lists for homes that don't exist and a conservative cost of $13 billion just to provide for those currently in need. But amid this daunting challenge, a new financial structure is emerging that could fundamentally transform how the country delivers affordable housing.

James Palmer, who has led the Community Finance team for six years, recently established the Community Housing Funding Agency (CHFA) in response to what he describes as an overwhelming crisis requiring an equally substantial solution. The agency represents a paradigm shift in how New Zealand approaches housing finance, drawing on proven international models while leveraging the country's growing pool of retirement savings.

The scale of the challenge

The numbers behind New Zealand's housing crisis are sobering. With nearly $5 billion spent annually in government subsidies, despite worsening conditions the traditional approach has proven insufficient. James emphasises that the scale of the problem demands an equally ambitious response.

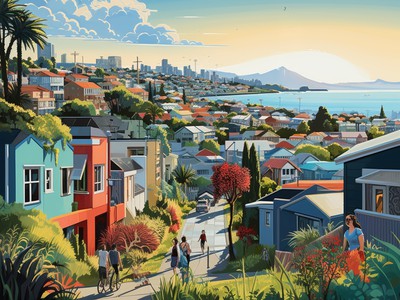

The crisis extends beyond simple supply shortages. New Zealand currently has less than 5% affordable housing stock, similar to Australia, placing both countries at the top of global affordability crisis rankings. In contrast, the UK and France maintain 17% affordable housing stock, while the Netherlands achieve 30%.

What makes the situation particularly frustrating, according to James, is that New Zealand has never had more money available for investment. With $300 billion in funds under management nationally, and KiwiSaver alone representing $120 billion (projected to reach $200 billion by 2028), the resources do exist to make a significant impact.

Understanding the funding gap

The core challenge lies in what's known as the "funding gap" — the difference between what people can afford to pay and what landlords need to charge to make ends meet. For someone earning New Zealand's average income of $65,000, affordable housing should cost no more than $375 per week (30% of pre-tax income). However, market rents often reach $700-800 per week.

This gap has traditionally been filled through the Income Related Rent Subsidy (IRRS), where the government pays community housing providers the difference over a 25-year contract period. While this addresses the affordability issue for tenants, it creates another problem: community housing providers have been paying premium interest rates on the finance needed to build and purchase properties.

James explains that finance typically represents 60-80% of each new home's cost, making it the largest expense over the 25-year contract period. The inefficiency of having charitable organisations pay higher interest rates than individual homeowners creates a system where taxpayers fund this inefficiency while receiving fewer homes in return.

"Who goes out and borrows together half a billion dollars and instead of getting a discount pays a premium? And the real tragedy is we as taxpayers have been fitting the bill for that inefficiency."

The international blueprint

CHFA draws inspiration from successful models overseas, particularly Housing Australia, which launched simultaneously with Community Finance and has already delivered $4.9 billion worth of loans to community housing providers. The Australian model demonstrates the potential impact: they estimate savings of $850 million in interest compared to traditional bank lending.

The UK's Housing Finance Corporation, established in 1987, provides an even longer track record. After nearly four decades of operation, it manages over £8 billion worth of loans to housing providers, with 42% of its loan book still covered by legacy government guarantees.

These international examples highlight a crucial insight: successful housing finance systems require government, banks, fund managers, and charitable providers to work together rather than operating independently.

How CHFA works

The Community Housing Funding Agency operates as a financial intermediary, bringing together multiple funding sources to provide lower-cost finance to community housing providers. The structure includes partnerships with banks (particularly ANZ), a $150 million government facility, and bonds purchased by seven KiwiSaver fund managers.

This approach creates what James describes as a "circular reference" where New Zealand workers' retirement savings are invested in domestic, affordable housing projects. The model offers lower risk than purely private investments because government provides the revenue stream through housing subsidies.

The collective approach dramatically increases the sector's buying power. Instead of individual providers with $10 million balance sheets negotiating separately, CHFA brings together borrowers representing $2 billion in combined debt, making the sector significantly more attractive to institutional investors.

"When you're facing the KiwiSaver providers, you're suddenly a really attractive sector. And that means we can borrow more and more to deliver affordable housing. And we can also borrow at a lower cost."

The power of collective action

CHFA's impact extends beyond simple cost savings. The agency actively works with community housing providers on pipeline development, helping newer organisations learn from more experienced ones. This knowledge sharing addresses one of the sector's key challenges: varying levels of experience and capability across different providers.

Currently lending to 14 community housing providers (up from five the previous year), CHFA expects to work with over 20 organisations within the current year. This growth represents a significant coming together of the sector, creating opportunities for shared learning and standardised best practices.

The agency focuses on what James calls the "top 35" community housing providers — not necessarily the best in terms of service quality, but those managing the most properties and therefore responsible for 95% of IRRS-funded homes in the community housing sector.

"Instead of their buying power just on their own, they might have a $10 million balance sheet. When we put all of our borrowers together and who's coming on board, it will be $2 billion."

Financial structure and innovation

CHFA operates as a social enterprise, consciously maintaining lower profit margins than traditional banks to pass savings directly to community housing providers. The agency offers both floating and fixed interest rates, with the ability to provide fixed rates for longer periods than banks typically offer to the community housing sector.

Currently offering fixed rates from one to five years, CHFA expects to extend this to seven or 10 year fixed rates as the organisation scales. This longer-term certainty is particularly valuable given that government contracts typically run for 15-25 years.

The agency's bond programme and government support enable it to achieve investment-grade credit ratings, further reducing borrowing costs. James notes that Housing Australia's bonds now carry AAA ratings — higher than current US Treasury bonds following Moody's recent downgrade.

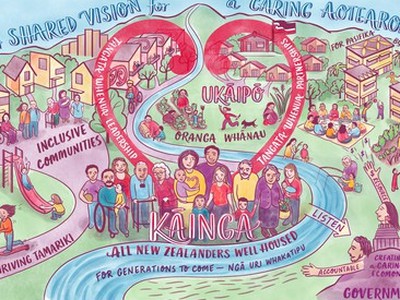

Addressing the broader housing continuum

While CHFA initially focused on IRRS-funded projects, the agency is expanding to support various tenure types, including progressive home ownership and other affordable rental programmes. This flexibility responds to growing recognition that different communities need different housing solutions.

The savings generated through lower interest rates create new possibilities across the housing continuum.

James calculates that a 1% reduction in interest rates saves approximately $400 per month on an average home loan — a significant amount that could enable new interventions or help more families transition from renting to ownership.

"For someone on a low income, $400 a month actually makes a hell of a difference. In fact, most of us, $400 a month would be quite nice."

Regional innovation and local solutions

Recent government announcements signal a shift toward localised decision-making, with regions like Rotorua and Hawke's Bay developing their own mixed-tenure approaches. CHFA's flexible financing model supports this trend by offering the same low rates regardless of funding source or tenure type.

This regional approach aligns with James's vision of "smarter contracts" that could allow tenants to remain in the same home even as their circumstances improve, with government subsidies adjusting accordingly rather than forcing disruptive moves.

The agency has observed significant regional variations in both housing costs and financing conditions, with some providers currently paying interest rates around 8% annually that CHFA can refinance at rates in the low 4% range.

Future prospects and challenges

Looking ahead, James identifies several key factors that will determine CHFA's success. Political continuity emerges as a crucial element, with housing challenges transcending normal electoral cycles but solutions requiring sustained commitment across multiple governments.

"It would be great if there was a little bit more commonality in where do we want to go and how are we going to do it? Because I think our three-year election cycle isn't helpful to this."

The agency's growth depends partly on additional government support, particularly guarantee mechanisms that could enable work with smaller or higher-risk providers. Currently, CHFA could work comfortably with approximately 30-40 community housing providers, but additional tools could expand this reach.

James emphasises that success requires continued collaboration across all stakeholders: community housing providers choosing to work with CHFA, government agencies supporting the model, and fund managers maintaining their investment commitment.

Building quality and efficiency

Beyond financing, CHFA's sector overview reveals significant opportunities for improving construction quality and efficiency. James highlights examples like Ōtautahi Community Housing Trust, which demonstrated mixed-tenure developments with an average build cost of $404,000 (excluding land) for high-quality one to four-bedroom homes.

This focus on building standards addresses long-term sustainability concerns. James notes the false economy of deferred maintenance, pointing to deteriorating pensioner flats and former Housing New Zealand properties as evidence of what happens when revenue streams don't support proper upkeep.

"We professionalise long-term maintenance. It's extraordinary if you're in a role like mine, seeing some of the pensioner flats and old Housing New Zealand houses that were left just in a dilapidated state."

The path forward

The Community Housing Funding Agency represents more than just a new financing mechanism — it embodies a fundamental shift toward collaborative, efficient approaches to addressing New Zealand's housing crisis. By bringing together retirement savings, government support, and community housing expertise, CHFA creates a sustainable model that could transform how the country delivers affordable housing.

Success will require sustained effort across multiple dimensions: continued political support, sector collaboration, and ongoing refinement of financing and delivery mechanisms. But the foundation now exists for addressing the housing crisis at the scale it demands.

"I think every person in the sector would agree that, you can in the morning be optimistic and in the afternoon be pessimistic. But I think it's about, you know, just remembering what we can achieve in a year or five years is a lot more than we probably give ourselves credit to do."

As CHFA continues to develop and scale its operations, the agency offers a blueprint for how New Zealand can leverage its financial resources to create the affordable housing supply its people desperately need. The challenge remains enormous, but for the first time in decades, the tools and structures exist to address it at the required scale.

James Palmer is Chief Executive of the Community Housing Funding Agency (CHFA), a social finance group supporting affordable housing across New Zealand. With a background in economics and investment, he leads CHFA's work with providers and iwi to deliver long-term, impact-focused finance for quality homes.