We don't really have an economy; we have a housing market with bits tacked on.

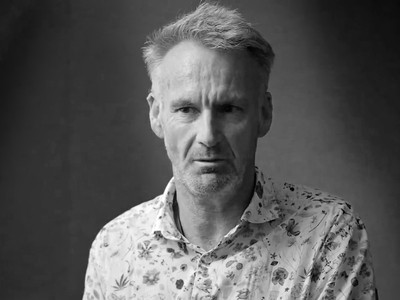

Bernard Hickey, journalist and editor of the influential newsletter 'The Kākā', offers a compelling diagnosis of New Zealand's economic and social woes through what he calls the "housing theory of everything."

He argues persuasively that the severe shortage of affordable, warm, dry, and healthy homes is at the heart of almost all significant issues facing the country, from cost-of-living crises and health problems to rising crime rates and declining productivity.

New Zealand's housing situation isn't just tough — according to Hickey, it's amongst the worst globally, due to decades of inadequate housing policies and underinvestment. "We don't really have an economy; we have a housing market with bits tacked on." he asserts.

How did we get here?

He takes us back to the mid-20th century, when New Zealand governments actively participated in housing development, regularly building 12 to 15 homes per thousand people annually during the 1950s-1970s. This proactive stance involved substantial public investment through entities like the Ministry of Works, creating thriving new suburbs and crucial infrastructure.

However, significant ideological shifts in the late 1980s and early 1990s transformed this landscape. A strong move towards smaller government, lower taxes, and reduced public debt drastically curtailed state involvement in housing.

From building more than 10 homes per 1,000 population in the 1970s, New Zealand now struggles to reach even four or five.

Crucially, the failure to implement a capital gains tax in 1989 left a legacy of speculative property investment. As Bernard points out, subsequent governments continued to prioritise low government debt and tax cuts over critical investments in public infrastructure and housing.

These policy choices dramatically reduced housing construction rates and significantly impacted affordability. According to Bernard, these decisions are now woven into New Zealand's political and economic DNA, creating a profound resistance to change despite growing awareness of their negative impacts. "From building more than 10 homes per 1,000 population in the 1970s, New Zealand now struggles to reach even four or five."

The cost of financial incentives

Over recent decades, financial incentives in New Zealand have increasingly favoured property investment rather than productive economic activities, significantly inflating house prices and rents. He reveals that a substantial portion of bank lending has been directed to property investors, exacerbating wealth inequality and creating a deeply unlevel playing field.

For those who managed to buy homes, especially investment properties, the returns have been extraordinary. He illustrates a troubling scenario: investors leveraging equity in their homes, enjoying tax-free capital gains, and building substantial wealth at the expense of productive business investments. This dynamic, he argues, entrenches economic inequality and reduces opportunities for meaningful growth and productivity.

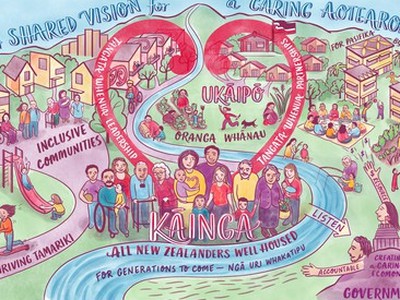

Reimagining New Zealand's future

Bernard advocates a fundamental shift in policy direction. He proposes implementing a land tax on residential-zoned property, rather than simply a capital gains tax on rental properties. This measure would incentivise denser housing development and discourage speculative land banking. Additionally, he calls for greater use of the Crown's robust balance sheet to invest in large-scale affordable housing projects, infrastructure, and social services. He criticises current fiscal conservatism rooted deeply in the New Zealand Treasury, suggesting it's preventing meaningful investment in critical areas. Bernard underscores the urgent need for policymakers to rethink outdated ideological commitments, embracing more substantial government participation in the economy.

200 New Zealanders a day are getting on an A320 to Sydney or Melbourne or Brisbane...

He closes with a poignant reflection on the social cost of New Zealand's housing policies: the growing exodus of young, skilled New Zealanders to Australia. With around 200 citizens leaving daily, often including entire families, he warns of a long-term demographic and social crisis unless urgent reforms are undertaken.

To address this crisis, Bernard emphasises the importance of government-backed initiatives that offer stability and affordability in housing, thus enabling families to build their futures in New Zealand. He also advocates for diversification in housing solutions, suggesting a blend of government and community-led projects as a more resilient and effective approach.

We need to use the Crown’s balance sheet to invest in infrastructure and affordable housing.

Bernard Hickey's insights challenge New Zealanders and their policymakers to confront uncomfortable truths and take courageous steps towards a more equitable and sustainable future. His analysis provides a roadmap that, if followed, could help reverse decades of damaging policies and build a more cohesive, productive, and hopeful society.

This article is a brief summary of the full interview. Be sure to use watch the full interview.

NZ Multiple property owners – Residential property holdings (2016–2024)

| Year |

1 Property |

2 Properties |

3–4 Properties |

5–9 Properties |

10+ Properties |

| 2016 |

1,030,000 |

157,800 |

56,300 |

13,400 |

3,260 |

| 2018 |

1,067,000 |

169,200 |

61,500 |

15,200 |

3,680 |

| 2020 |

1,094,000 |

176,900 |

66,400 |

16,900 |

4,090 |

| 2022 |

1,104,000 |

184,600 |

71,800 |

18,400 |

4,540 |

| 2024 |

1,115,000 |

191,900 |

76,300 |

19,900 |

4,890 |

Percentage increase since 2016:

| Category |

Increase |

| 1 Property |

8.25% |

| 2 Properties |

21.61% |

| 3–4 Properties |

35.52% |

| 5–9 Properties |

48.51% |

| 10+ Properties |

50.00% |

New Zealand household wealth (NZD – Billions)

| Category |

Value (NZD billions) |

| Residential real estate |

$1,620 |

| Commercial real estate |

$331 |

| NZ Super & KiwiSaver |

$193 |

| NZ Listed stocks |

$167 |

Social / affordable housing stock as a percentage of total housing

(Sorted: Highest → Lowest)

| Country |

Approximate Share of Total Housing Stock |

| Singapore |

80% |

| Netherlands |

29% |

| Austria |

24% |

| Denmark |

20% |

| France |

17% |

| United Kingdom |

16% |

| Finland |

13% |

| Australia |

4.1% |

| Norway |

4.0% |

| United States |

4.0% |

| New Zealand |

3.8% |

| Canada |

3.5% |

| Spain |

1.0% |

Percentage increase in NZ property owners by holding size (2016–2024)

| Holding Size |

Percentage Increase (2016–2024) |

| 1 Property |

+8.3% |

| 2 Properties |

+21.6% |

| 3–4 Properties |

+35.5% |

| 5–9 Properties |

+48.5% |

| 10+ Properties |

+50.0% |