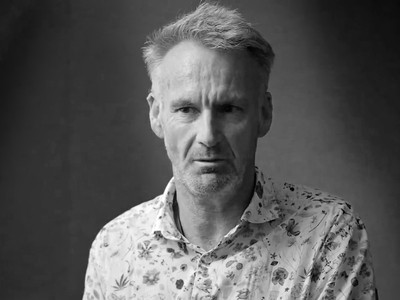

Jim Boult arrived in Queenstown in 1982 when the population was 3,000 and people called it a "one-dog town." After 42 years as a resident and six as mayor, he's fought a battle most councils won't touch: forcing developers to provide affordable housing in exchange for development rights. His weapon of choice, Inclusionary Zoning, has delivered results. His warning about what happens without intervention comes from watching Aspen, Queenstown's sister city, become a place where almost nobody who works there can afford to live.

The problem nobody denies

"For many, many years we've had a housing problem here," Jim states plainly. But he's quick to correct assumptions. "People talk about housing as though it fits under one headline. It's not." The district serves migrant workers doing six-month OE stints, workers on three-to-five-year visas, and people wanting permanent residence. Each group faces different challenges, none of them small.

The numbers tell a brutal story. Average house prices sit around $1.75 million. In family suburbs like Shotover Country and Lake Hayes Estate, the cheapest house costs approximately $1.2 million. Nice four-bedroom homes with double garages routinely exceed $2 million.

"My problem with this is that we need people to live here and work here," Jim explains. "The policemen, the truck drivers, the people who work in the shops — if you're an ordinary income family with one and a half parents working, two or three kids, and you want to carry on a reasonable lifestyle, how on earth do you afford to buy at those sort of prices?"

His conclusion is unequivocal: "For the greater good of this place, we have to do something about it. This is not a nice-to-do, this is a must-do."

The State's retreat

Central government's contribution to the crisis frustrates Jim deeply. "There's an unfortunate presumption in the halls of government departments that Queenstown is full of rich folk and we can solve these problems ourselves without any input from central government." The reality? "A large portion of our population are struggling and they need some assistance."

Government owned state houses in Queenstown during the 1970s and 1980s, then sold them from the 1990s onwards "on the basis they weren't required." Jim's assessment: "Short-term thinking."

But he doesn't place blame solely on Wellington. "This is not just a government issue. This is a council issue, a government issue, and an employer issue to resolve. And property owners, property developers have also a big part to play in this."

The fight nobody else would take

When Queenstown Council decided to pursue Inclusionary Zoning in the Unitary Plan, Jim wrote to every council in New Zealand with a blunt message: "Bottom line is we're going to have this fight but you guys better help out here because you're going to get the benefit if we win."

The fight Jim references is real and ongoing. Queenstown Lakes District Council knew implementing Inclusionary Zoning would provoke fierce resistance. Property developers naturally oppose requirements to provide affordable housing. The legal and political costs are substantial. Most councils, faced with such battles, choose easier paths. "Why should a small council be having this fight and meeting the cost of it?" He says when asked if national legislation would help. "This is something that should be national. It's a bit silly that it's not."

His frustration with the term "Inclusionary Zoning" is palpable. "I'd much rather it had a different name because I've mentioned the word Inclusionary Zoning and people have zero idea what I'm talking about." But the mechanics matter more than the branding.

Under Inclusionary Zoning, approval comes with a condition: a percentage of sites created, or their equivalent value, transfers to Queenstown Lakes Community Housing Trust for affordable housing programmes.

"There's a cost to that and property developers will argue that they will need to pass on the cost into the sections that are created for other people," Jim acknowledges. "There's a downside to everything and I think the downside is low compared to the value created in the number of sections that will be made available."

The QLCHT plays a crucial role, ensuring properties reach appropriate recipients and preventing quick flips for hundreds of thousands of dollars profit. "That happened in the past with other housing programmes that we had in the district," Jim notes. They've moved beyond that now.

Defining key workers

Who benefits from these programmes? His answer reveals his values. "Define me what is a key worker in this district. It can be anything from a nurse to somebody who cleans pots in the restaurant because they're all key workers. The economy depends on them all being here. People's welfare depends on them being here. So it's difficult to say who's important or not. But anyway, everybody's important. Everybody should be able to have a place to live."

Then he makes a statement remarkable for a former property developer and businessman: "Call me a 'Chardonnay Socialist', but life is more than working three jobs to be able to afford a place to live. A family has a reasonable expectation that they'll have a place to live that they can afford and yes, you have to work hard to get there, but they've got to be able to have a bit of time off and go and play some sports or go for a walk in the hills in the weekends and not be simply working every day of the week to put a roof over your head."

It's a philosophy that underpins everything Queenstown has attempted with housing policy, a rejection of pure market logic in favour of something closer to human dignity.

The Secure Home innovation

The connection between Inclusionary Zoning and Queenstown's Secure Home model illuminates how policy innovation actually works. In 2018, Jim convened a mayoral taskforce on housing, bringing together bank CEOs, property developers, and economists, all volunteering their time to solve the problem.

"The best idea we came up with was Secure Home," he recalls. "And the promise of Secure Home is that it is a nest, not a nest egg." The model is elegant. Land stays with the trust in perpetuity. Buyers purchase houses but not land, paying peppercorn rent on the ground beneath. They're there forever, not subject to landlords raising rent $100 per week or demanding they vacate within a month. The house doesn't increase in value beyond inflation, meaning no capital gain speculation. But mortgage payments build equity, creating value for families.

The trust has created approximately 60 to 70 such properties. The goal is 1,000 across the district. Inclusionary Zoning provides the land supply making that goal achievable.

"You would not believe the number of folk who have ended up in one of those Secure Homes who still stop me when I'm in the supermarket and say thank you, I'd have never got a home if it wasn't for this," Jim says, emotion evident in his recounting.

When families need to move for work or other reasons, houses sell back to the trust at the same inflation-adjusted price, remaining perpetually affordable compared to the open market. "It really, really is a wonderful product and being honest with you, I'm surprised more councils haven't picked up on it. I'm surprised central government haven't picked up on it."

The Aspen warning

Jim had coffee yesterday with the mayor of Aspen, Queenstown's sister city. The conversation offered a glimpse of dystopia. "That's probably the ultimate model that we'd end up with if we don't address this," he warns. "Aspen is a wonderful place, but it is Queenstown on steroids when you come to affordability."

The mayor reported day skiing passes costing approximately $400 US, minimum accommodation $400 US per night, $100 steaks. Almost nobody who works in Aspen lives there. They commute from satellite towns, precisely what Jim fears for Queenstown if housing intervention fails. He states "The ultimate outcome if that happens is that no one who works in Queenstown will live here. They will live in satellite towns like Cromwell, like Kingston, elsewhere, and not live in the town." Some might shrug and accept that outcome. Jim rejects it completely.

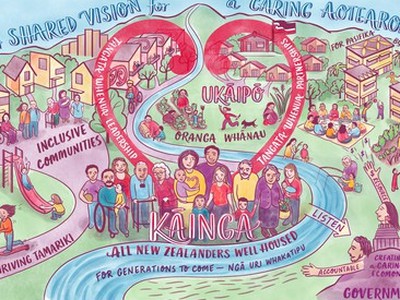

The value of mixed communities

"I'm a strong believer in a community that is made up by all sorts of people at all levels," he states. A functioning town has a community that's made up of all those subsections." The alternative, mass developments of assisted accommodation segregated from market housing, creates stigma. He knows firsthand. Growing up in Invercargill, his parents bought their first house on a street where government bought properties on the opposite side. "You ended up with a street that had a dividing line down the middle. The people who owned their own houses on this side and the people who were in state houses on the other side. It created that stigma, which is just silly. Whereas if they'd been intermixed, would have been a far better model."

Inclusionary Zoning naturally creates pepper-potted distribution, building integration into the system rather than fighting against it later.

The free-market believer's exception

Jim describes himself as "the biggest believer in free markets that you could find." But he adds immediately: "Some things need intervention and housing is one of those."

His evidence is historical and stark. Houses created per capita in New Zealand through the 1950s, 1960s, and into the 1970s kept pace with population growth. "Somewhere about the end of the 70s, I think it was back in the Rogernomics days, the graph went down like that and we've been below the line ever since."

Getting back above that line requires action. "I'm not the world's expert on this and I'm not going to tell people how to do it, but it needs to happen and the only tool I'm seeing that's going to help us along the way at the present time is Inclusionary Zoning."

When asked what he'd tell developers fighting the initiative, his response is respectful but firm: "I would say I understand exactly your point of view, I understand where you're coming from but this is about the greater good of the district and I'm sorry but it is a pill that's going to have to be swallowed."

The battle worth fighting

Queenstown Lakes District Council didn't have to fight for Inclusionary Zoning. Most councils, faced with developer opposition and legal costs, choose paths of less resistance. Jim and his council chose differently, knowing other councils would benefit if they won but wouldn't help with the fight.

The results speak clearly. Secure Home residents stop Jim in supermarkets to express gratitude. Families have security they never thought possible. The model works, proven over years of implementation. Capital gains speculation gives way to stable homes where children grow up without constant disruption.

"It's a massive problem for New Zealand, massive problem locally here," he concludes. But the solution exists, tested and proven in one of the country's most expensive housing markets. What's required isn't innovation or new ideas. It's political will to implement what works, national legislation removing the burden from individual councils, and collective commitment to the greater good over individual windfall gains.

The choice is clear. Queenstown can become like Aspen, a beautiful place where workers commute from satellite towns, community cohesion fractures along economic lines, and diverse, integrated neighbourhoods become memories of when things were different. Or it can remain a functioning community where people at all income levels live, work, and raise families together, all of them belonging, all of them with a secure home.

Jim Boult spent six years as mayor fighting for the latter. The question is whether the rest of New Zealand will join the fight or watch the divide grow wider until intervention becomes impossible and communities are lost to pure market forces that never intended to house everyone fairly.