Professor Laurence Murphy has spent decades studying how property developers make decisions and what drives housing markets. His conclusion is unequivocal: markets produce market outcomes, not affordable housing.

The Value Uplift Nobody Earned

At the heart of Professor Murphy's argument sits a simple economic reality: planning creates value, and most of that value flows to people who did nothing to earn it.

When planning permission transforms a greenfield site into residential development, or allows increased intensification on existing land, massive value uplift occurs. That uplift flows primarily to landowners. Larry emphasises "The landowner is getting money for nothing. With the stroke of a pen, there's a value uplift. They haven't invested in the land."

Planning operates in the public interest. When it creates opportunities for private profit, the question becomes: how much of that publicly created value should return to public benefit? Inclusionary Zoning offers one mechanism, requiring developers to provide affordable housing as part of developments, effectively capturing some windfall gains for social good.

The International Evidence Is There

Murphy's research spans jurisdictions globally, and the evidence is clear: Inclusionary Housing works when properly implemented. Since the 1970s, the United States has used Inclusionary Zoning to secure affordable housing. In the UK, particularly since the 1990s, it has become the primary mechanism for affordable housing delivery through the private sector.

The scale in Britain is remarkable. Inclusionary Housing currently accounts for approximately 50% of all new affordable housing in the UK. In 2020 alone, levies on developers amounted to £7 billion, of which £4.7 billion went towards affordable housing provision. He states "In 2020, UK levies on developers produced 44,000 affordable houses. They still make profit."

But implementation requires something New Zealand increasingly lacks: a strong planning regime empowered to act in public interest. "Unfortunately in New Zealand, we've probably since 2013 decided that planning is bad and most ministers are trying to reduce the role of planning," he notes.

The Market Fantasy

For those who believe unfettered markets will solve affordable housing challenges, his response is blunt: "Market housing provides market outcomes. It provides a market for those who pay the most. It's not designed to produce affordable housing, it's to produce profitable housing."

He hasn't found evidence anywhere globally that markets left to themselves deliver affordable housing for low-income families. Thirty-five years of New Zealand's market-driven approach provides clear results: severe unaffordability for growing numbers of households.

The financialisation of housing has deepened this problem. What were once simply homes have become pension plans and capital gains vehicles. People make more money from untaxed house price appreciation than they ever will from income.

Transparency in the UK

Britain's Section 106 system demonstrates how systematic value capture can function fairly and transparently. When developers approach councils with proposals, planning agencies examine all development assumptions using standard financial models.

Councils assess gross development value, costs, profit margins (typically 20%), and land payments. They then determine whether affordable housing requirements can fit whilst maintaining reasonable developer returns. If developers disagree, then negotiations commence. One critical insight he notes is that Inclusionary Housing reduces overall development value but doesn't change profit ratios. What it does is reduce land bid prices.

Development Feasibility

One barrier to implementing Inclusionary Housing in New Zealand is technical understanding. Developers, politicians, and public alike must understand that requiring affordable housing reduces overall development value without changing profit percentages.

A common fear is that developers will jack up prices on market-rate homes to compensate for affordable units. "The experience is your price is set by the market, by the local market, not by what you think you can do," he counters.

This technical reality must be communicated clearly to developers. He notes, "What we're trying to do is take some of that value uplift in the land, take it away from just a freebie to landowners who just own land, may not have done anything, and provide it for a positive outcome."

He points out "This is providing affordable housing, it is providing houses for nurses, police officers, teachers," he argues. "It's not giving away housing and taking their profit."

Cost Reduction Fallacy

One of Larry's most passionate arguments concerns the persistent fallacy that reducing developer costs, such as the planning process, will help deliver affordable housing.

"That's a fallacy," he states emphatically. When costs decrease, developers don't reduce prices. They increase land bids. The development financial model works backwards from market prices. "If you reduce my costs, I increase twenty developers competing for sites, each reducing costs, bid each other up to the point where they still make profit. Prices remain at market levels."

No one releases below market level houses to a market in a sub-market because they know they can push it to the very edge," he observes. "If it's a million dollars in the neighbourhood, that's where I aim to produce and I can sell it at a million dollars."

The Role of Government

New Zealand's experience with Queenstown Lakes District demonstrates both possibility and vulnerability. Substantial affordable housing volumes have been delivered through inclusionary mechanisms, but the programme faces ongoing litigation, labelled a "tax" by opponents.

He sees clear need for central government intervention and legislative support. Internationally, countries maintaining state housing provision are the ones meeting lower-income housing needs.

Since governments removed themselves from direct provision, prices have grown massively. "Partly because effectively you're reducing the supply of housing," he explains. "So it's all been left to the private sector."

The tax label interests him. "Developers deal with tax all the time, GST. They do all kinds of taxes, doesn't stop them from producing housing." If everyone in Queenstown must provide affordable housing but nobody outside the district does, competitive disadvantage emerges. National frameworks create level playing fields.

The Planning Backlash

The last 10 to 15 years have seen strong movement suggesting planning represents cost that should be removed. This represents historical amnesia. Pre-planning Victorian Britain showed what unregulated development produces: clashing land uses, negative externalities, poor outcomes for ordinary people.

Political rhetoric about releasing more land represents another fallacy he challenges. "Land can't be developed unless it's beside a road. Land can't be developed unless there's a sewerage system, unless there's water," he points out. Infrastructure costs money. Taxpayers and ratepayers fund that infrastructure "Who's paid for that infrastructure? Taxpayers. Ratepayers. That's the public purse." He asks: "If the land has been serviced by the public, should there be a return to that? Should there be some form of affordable benefit that benefits the public?"

The Treasury Mindset

Larry identifies deep-seated ideological barriers within New Zealand's economic policymaking institutions. The trauma of the Muldoon era embedded particular mindsets in Treasury: borrowing is bad, government spending is bad, even for infrastructure investment.

Most undergraduate economics courses don't examine property. They explore competitive industries producing homogeneous products. But every property site is heterogeneous, unique, effectively a monopoly. He notes: "If poor people are in poor housing, they have additional costs on our education, health, and judicial systems."

Applying standard economic assumptions to property development produces misunderstandings and wrong conclusions. "We have a group of people who are brought up and educated in a system that tells you spending is bad, and they have limited understanding of the economics of development," he argues. The irony is that during crises, 2008 and COVID, governments suddenly remembered Neo-Keynesianism: states can spend, can invest in infrastructure.

Social Investment, Not Charity

Housing low- and middle-income people in good housing reduces costs across education, health, and justice systems. "We know that if people are in poor housing they have additional costs," he explains. "If you can put people into good housing then they have positive outcomes."

This isn't radical new thinking. Post – World War II, it was called public education, public hospitals, public housing. Social investment benefiting entire societies. Thirty per cent of UK housing in 1973 was state-owned. "After World War II, it was called public education, public hospitals, and public housing. It's not new."

Larry's students' changing attitudes reveal how far thinking has shifted. Twenty years ago, they generally agreed social housing tenants should have tenancy for life. Seven years ago, they said no. Why? "Because we don't have security of tenure in the private sector," they explained. Rather than extending security to private rental, they preferred removing it from social housing.

Developer Logic

His research into developer behaviour reveals another uncomfortable truth: developers produce houses when prices rise. When prices stall or drop, production stops. "The logic is that if I'm building something, I will continue to build it," he explains. "But we know the reality is the developers borrowed money. Soon as those prices start to drop or peter out, their financial model has gone haywire and the bank pulls the funding."

Banks require pre-sales, profit margins, price certainty.

The Clear Path Forward

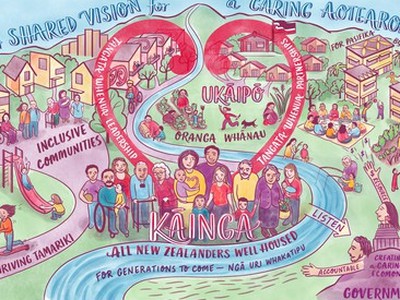

His policy prescription combines multiple elements. State provision retains essential roles. Cheap government finance enables scale. But Inclusionary Housing represents crucial additional tools.

Properly implemented with technical understanding, clear rules, national frameworks providing certainty, and careful introduction managing transition, it captures publicly created value for public benefit without destroying development viability. "There is a political commitment, you can enact change," he states. Britain proves it works at scale and the US demonstrates multiple implementation paths.

The challenge isn't primarily technical. It's ideological, embedded in assumptions about markets, property, housing, government roles. He notes. "We need political boldness to reassert that social investment produces better outcomes for everybody."

Breaking these patterns requires political boldness, public narrative shifts, willingness to challenge embedded assumptions. It requires recognising that housing serves use value, not just exchange value. That security of tenure benefits everyone. That public investment produces returns across education, health, social cohesion. "Maybe we can choose some good outcomes," he suggests. The possibilities exist. International evidence demonstrates workable models.

What's required is will, technical understanding, and fundamental recognition that markets will never voluntarily deliver affordable housing. They're not designed to. Inclusionary Housing offers tested tools for capturing value planning creates and redirecting it towards housing all people adequately.

The question isn't whether New Zealand can do this. The question is whether New Zealand will choose to, whether political courage exists to challenge embedded ideologies and implement policy serving genuine public good rather than abstract market faith contradicted by 35 years of evidence.