From the Quod office in London, overlooking some of Britain's most ambitious urban regeneration projects, Claire Dickinson reflects on a quarter-century career navigating the intersection of development viability and community benefit. As leader of Quod's development economics team, she's negotiated affordable housing on schemes from Battersea Power Station to the London Olympics — projects that have helped deliver hundreds of thousands of homes for British families who would otherwise be priced out of their communities.

Housing has to be viewed as infrastructure. And it can't be party political.

The mechanism that makes this possible is Section 106 of the 1990 Town and Country Planning Act, a policy framework that has quietly become Britain's single largest method of delivering affordable housing since 2015. Through this system, nearly 140,000 affordable homes have been delivered in just the past five years alone, with developers contributing approximately £10.8 billion towards affordable housing provision, infrastructure, and amenity enhancements.

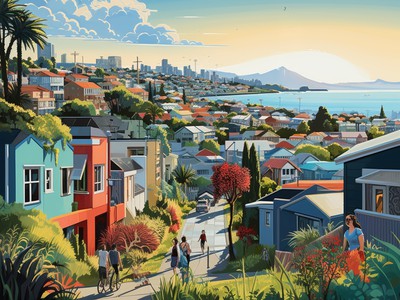

For New Zealand, where Inclusionary Housing remains sporadic and legally vulnerable, the UK's experience offers both inspiration and practical lessons about what works when policy ambition meets market reality.

From principle to practice

Section 106's elegance lies in its fundamental premise: when planning permission creates private value, the community should share in that benefit. "Housing has to be viewed, particularly affordable housing, alongside other types of housing, has to be viewed as infrastructure," Claire emphasises. "And it can't be party political."

The system works through legal agreements attached to planning permissions, typically requiring that 30-50% of homes in new developments be designated as affordable housing. In London, that figure reaches 50% — a requirement that might seem impossibly ambitious to New Zealand councils nervously contemplating single-digit percentages.

Yet the system has delivered at extraordinary scale. Since the first Section 106 affordable home completions in 2000-01, the mechanism has grown to account for 44-51% of all affordable housing delivery in England in recent years. This represents not marginal gains but the cornerstone of Britain's affordable housing supply.

The art of negotiation

What makes Section 106 effective isn't rigid prescription but structured flexibility. Claire's career has been built on understanding that "the more you get hearts and minds together, the outcomes are brilliant." Rather than imposing universal mandates that render developments unfeasible, the UK system creates space for negotiation within clear national frameworks.

The Shell Centre development in Lambeth exemplifies this collaborative approach. Faced with a very high-density site between Waterloo Station and the river — unsuitable for the family-focused affordable housing the borough needed — developers and council together identified an alternative solution. By building affordable homes on nearby council land at Lollard Street instead of forcing them into the Shell Centre towers, she explains "we got three times the number of homes by using the money that would have been on site to deliver in that way, and the outcomes were so much better."

Can you give us the gift of negotiation? When hearts and minds come together, outcomes are brilliant.

This flexibility extends to tenure mix, location, and delivery mechanisms. Some developments provide affordable homes directly on-site. Others contribute financially to off-site provision where that delivers better outcomes for families. The key is that outcomes, not rigid processes, drive decisions.

"Can you give us the gift of negotiation?" she asks when approaching councils. "We understand your policy. We understand what your policy is trying to achieve. We think we can achieve that in a bigger, better way. So please, can we just have a conversation?"

Capturing value, not killing development

The perpetual tension in Inclusionary Housing is between capturing community benefit and maintaining development viability. Britain has wrestled with this balance for two decades, learning hard lessons about what works.

Initially, developers buying land at market prices would then claim they couldn't afford to deliver affordable housing. The system evolved to prevent this gaming. "You can pay more for land, that's up to you," she explains, "but when you come to us and put together a financial appraisal that says you can't afford to deliver our ask in terms of affordable housing, you can only allow existing use value plus a little bit of profit."

This land value capture mechanism ensures windfall gains from planning permission flow primarily toward affordable housing rather than inflating land prices. It's a lesson painfully learned: without controlling what developers can claim as acceptable land costs in viability assessments, the community benefit gets captured by landowners rather than converted into affordable homes.

National framework, local application

Perhaps the most critical lesson from Britain's experience is the essential role of national legislation. "Absolutely critical," she states emphatically when asked about centralised policy frameworks. Without national backing, each local authority fights developers individually through expensive appeals and Environment Court challenges. Precisely the dynamic that makes New Zealand councils nervous about adopting Inclusionary Housing.

Absolutely critical. Without national policy, every authority fights developers individually through expensive appeals.

Britain's national planning policy establishes housing as the number one policy objective and sets clear expectations that developments will deliver mixed communities including affordable housing. This removes the question of whether Inclusionary Housing is legitimate and shifts debate to how it should be implemented locally.

She notes, councils and communities need permission to innovate within stable frameworks rather than reinventing basic principles through costly legal battles.

A pragmatic approach to mixed-tenure

British experience has also challenged assumptions about mixed-tenure development. The instinct to 'pepper-pot' affordable and market homes throughout every building by mixing rich and poor, door-by-door, sounds progressive but can create perverse outcomes.

Mixed communities need equal access to amenities and quality design, not hyper-engineered tenure mixing.

"If we start to focus on the perception of the person walking down the street rather than the perception of the person that's living in the home, then things start to fall apart," she argues. Forcing rigid integration within individual buildings adds management complexity and cost, ultimately reducing the number of affordable homes that can be delivered.

Better outcomes come from ensuring affordable housing is well-distributed across communities with equal access to amenities, quality design, and good space standards, without obsessing over which specific building contains which tenure. "Good places that live well are designed in a way that integrate really effectively," she observes, pointing to organically-grown British cities where diverse communities function without hyper-engineered tenure mixing.

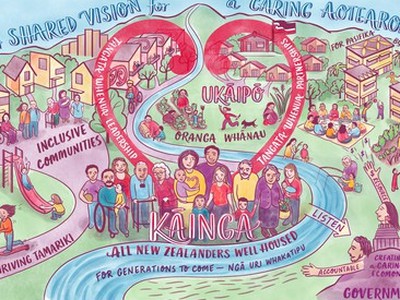

Creating a housing continuum

Looking forward, she sees opportunity in what she calls the "middle sector" — housing that bridges traditional affordable housing and open market provision. Rather than polarising into subsidised and market extremes, she advocates creating a continuum where "people in affordable housing can move into that middle space, and from that middle space, they can move to private market housing."

Create overlap between

market and affordable housing. Give people a ladder of opportunities.

This requires collaboration with private investors interested in entry-level rental housing. A sector that could absorb many households currently dependent on heavily subsidised provision if given appropriate policy support. "Look to the market to help you," she urges. "The market can actually deliver really effective entry-level housing" with modest government backing such as rent underwriting or time-limited requirements.

The goal isn't to trap people in affordable housing but to "give people an opportunity to move out of affordable housing and to meet their own housing needs on the open market." She stresses. This requires thinking about housing not as an end state but as a dynamic system with movement and progression.

Lessons for New Zealand

For New Zealand councils watching Queenstown Lakes' Inclusionary Housing experiment nervously, Britain's experience offers reassurance alongside complexity. Section 106 has delivered hundreds of thousands of affordable homes over two decades. A scale of success that validates the core principle of value capture for community benefit.

Yet that success has come through national legislation providing legal certainty, viability frameworks preventing land price inflation from capturing the benefit, and sophisticated negotiation replacing rigid prescription. As Claire's career demonstrates, the technical details matter enormously in converting policy aspiration into actual homes for actual families.

The message is both encouraging and challenging — Inclusionary Housing works at scale when properly designed, but 'properly designed' requires investment in frameworks, expertise, and institutional capacity that go far beyond simply writing percentage requirements into district plans.

Britain spent twenty years learning these lessons. New Zealand has the opportunity to learn from that experience rather than repeating every painful iteration. The question is whether we have the political will to provide the national legislative backing that would enable councils nationwide to capture community value for community benefit — turning windfall planning gains into perpetual affordable housing as Britain has done, but learning from both their successes and their stumbles along the way.