With snow-capped mountains reflected in crystal lakes and a thriving tourism economy, Queenstown Lakes District presents a picture-perfect postcard of New Zealand. Yet behind this scenic beauty lies a housing crisis that threatens the very workers who keep this destination alive. The median house price of $1.7 million stands in stark contrast to the average household income of $80,000 among those seeking housing assistance, a gap that would be insurmountable without innovative intervention.

For almost 20 years, the Queenstown Lakes Community Housing Trust (QLCHT) has been demonstrating a solution that works: Inclusionary Housing. Through this mechanism, the trust captures a portion of the value uplift created when land is rezoned from rural to residential, converting windfall gains into perpetual housing affordability for local workers. With over 1,200 households currently on their waiting list — representing thousands of individuals — QLCHT's work has never been more critical.

A crisis sharpened by tourism

The housing challenge in Queenstown Lakes differs from other New Zealand regions in both scale and dynamics. Julie Scott, QLCHT's Chief Executive, explains how the district's tourism economy creates unique pressures: "During COVID, we saw rental properties come off short-term visitor accommodation and back into the long-term rental pool. When borders reopened, those properties went straight back to short-term accommodation, and our families were left wanting."

This volatility has intensified what was already a severe shortage. The trust's waiting list has grown significantly in recent years, particularly post-pandemic. These aren't seasonal workers or transients; QLCHT serves only those with residency status who are committed to putting down roots in the district. "We're focused on long-term residents," Julie emphasises, "the police, teachers, nurses, tradespeople, service workers, hotel workers, everyone who makes this community function."

The organisation operates across a housing continuum, from public housing for those on very low incomes to assisted ownership for households earning up to $130,000 gross annual income. This breadth allows them to serve everyone from seniors on pensions to working families who simply cannot compete in a market where rural land suddenly becomes worth millions with a zoning change.

Inclusionary Housing: capturing community value

At the heart of QLCHT's success lies a deceptively simple principle: when public decisions create private wealth, the community should share in that benefit. "Every time a landowner has gone to council and said they want land rezoned from rural to residential, our council has been saying, 'We're happy to do that, but if we enable that value uplift, we want the community to share in a small amount,'" she explains.

Historically, this has meant approximately 5 percent of new sections created through rezoning come to the trust, though some developments have contributed as much as 10 or even 12.5 percent. The trust then holds these land contributions in perpetuity, building homes that remain affordable across generations through a retention mechanism that prevents speculation and wealth extraction.

This isn't a radical new concept. It's standard practice in many developed nations. In London, 50 percent of new developments must be affordable. In Aspen, Colorado, Queenstown's sister city, similar mechanisms have enabled the creation of substantial housing stock for workers. "The issues are incredibly similar," she notes of their conversations with Aspen officials, "these tiny towns, these really high-end properties, and the same problems around housing workers."

What makes QLCHT's model particularly elegant is its minimal impact on development economics. The value uplift from rezoning is often enormous. Julie cites a recent example where council provided land valued at $10 million for just one dollar. Sharing 5 percent of sections from such windfall gains represents a small fraction of the total benefit developers receive from the stroke of a council pen changing zoning designations.

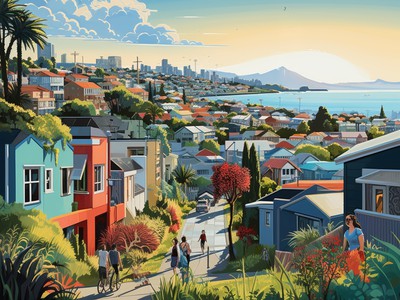

Mixed-tenure communities: breaking down barriers

One common objection to community housing is the fear of concentrated disadvantage: the spectre of 'ghettos' that has plagued some large-scale social housing developments. QLCHT has deliberately designed against this outcome through mixed-tenure developments that integrate households across the economic spectrum.

The Toru Apartments in Frankton provide a compelling example. In this six-storey, high-density development, QLCHT purchased 50 of 78 units. Of these, 15 are in public housing, while the remainder are in assisted ownership programmes. The other 28 units are in the free market — either private rentals or first-home buyers. "You can walk down the corridors and you won't know if the door opens to a public housing tenant or a first-home buyer," she says proudly. "There's so much evidence around the world that mixed-tenure communities provide really positive outcomes."

This integration extends throughout the district. Because Inclusionary Housing delivers land where new subdivisions occur, QLCHT's homes are spread across multiple developments rather than concentrated in single locations. The trust has completed approximately ten development projects of varying scales, from the 44-home development at Shotover Country to smaller projects in Arrowtown and Lake Hāwea. Currently, the major Tewa Banks development in Arrowtown is progressing, with 68 homes ultimately planned.

These aren't placeholders for future housing, they're functioning communities today. Through various programmes including Secure Home, their leasehold assisted ownership model, households purchase the improvements while QLCHT retains the land, operating effectively as a community land trust without formally adopting that designation.

The battle for permanence

Despite 21 years of successful operation and broad community, with most residents knowing someone who has been helped by the trust, QLCHT now faces a critical juncture. The organisation is working alongside local Council to have Inclusionary Housing permanently embedded in the district plan, but faces organised opposition from some members of the development community concerned about costs.

"Not all developers oppose it," she clarifies. "The very first developers who signed a deed in 2003 did so on a voluntary basis." However, the current plan change variation is anticipated to end up in Environment Court, creating legal costs for the Council and ratepayers. Precisely the kind of jurisdictional isolation that makes local authorities nervous about adopting Inclusionary Housing elsewhere.

This is where national legislation could transform the landscape. "If central government could legislate it and pave the way to make it easier, that would be an amazing outcome," she argues. Rather than each council fighting developers individually through expensive legal challenges, national legislation would establish a higher legal bar and provide clear authority for what is ultimately a reasonable community claim on publicly-created value.

Other councils around New Zealand are watching closely. "I've talked to so many councils who are really interested in our model," she notes, "particularly those with high-end properties and issues with housing their workers. They're waiting to see what happens with QLDC's plan change." National legislation would give these councils the confidence and legal framework to move forward without each facing isolated challenges.

The social cost of inaction

Beyond statistics and policy mechanisms lies the human reality of housing insecurity in one of New Zealand's wealthiest districts. She recalls morning bike rides past Lake Wakatipu: "You go past all these cars with tradies' work boots outside the front door and they're sleeping in there. It's not what we want and it's not a healthy community."

During winter, when temperatures plunge well below zero, the situation becomes desperate. The 'haves and have-nots' divide has sharpened dramatically since the trust's formation in 2007. "Without a capital gains tax, it feels like those haves will just continue to build their wealth while the have-nots will just continue to pay high rents and pay the mortgages of those lucky few," she observes. "It doesn't feel like the New Zealand we all grew up in and love."

The implications extend beyond individual hardship to community sustainability. When service workers cannot afford to live near their jobs, cafes struggle to stay staffed, schools face teacher shortages, and hospitals cannot maintain adequate nursing levels. The economic engine that creates Queenstown Lakes' wealth begins to sputter without the workers who operate it.

A viable path forward

QLCHT's future depends on two critical pillars: securing the Inclusionary Housing plan change and maintaining central government funding support. "It's very much reliant on that pipeline going through," she explains, " and on central government funding for progressive home-ownership loans, public housing, and affordable rentals."

The Trust's track record demonstrates what's possible when community housing providers receive appropriate support. Operating since 2007, QLCHT has helped hundreds of households while maintaining a portfolio of quality, energy-efficient homes across the district. Their Secure Home programme has won international recognition, including the Leading Innovation Award from the Australasian Housing Institute.

But the approximate 1,500 plus households on the waiting list represent a pipeline that requires sustained commitment. Some of these families have been waiting years for stability. Every delay means more workers leave the district, more children face housing instability, and more erosion of the community's social fabric.

National implications

For other regions considering Inclusionary Housing, Queenstown Lakes offers both inspiration and a practical roadmap. The mechanics are straightforward: when rezoning creates value uplift, requiring a modest portion of that gain to be contributed to perpetual affordable housing. The community land trust structure ensures these contributions compound across generations rather than enriching a single cohort.

The political economy is more challenging. Developers naturally resist any requirement that reduces their margins, even when those margins are enhanced by public rezoning decisions. Without national legislation, each council must fight this battle individually, facing expensive legal challenges and uncertain outcomes.

Yet the alternative, allowing housing unaffordability to hollow out working communities, poses far greater costs. As Julie frames her plea to developers: "We all live in the community and we want these people in the cafes serving us coffee, teaching our kids, staffing our hospitals. Share that value uplift created through rezoning, share a little bit of it with the community for the benefit of all."

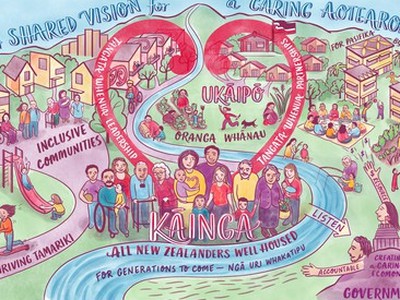

Community Housing Aotearoa and Te Matapihi are pushing for national Inclusionary Housing legislation precisely to resolve this dynamic. By establishing clear authority and consistent frameworks, legislation would enable councils nationwide to adopt what QLCHT has proven works. This means capturing community-created value for community benefit, building mixed-tenure developments that integrate rather than segregate, and maintaining perpetual affordability through land trust structures.

For New Zealand to remain the broad-based home-owning democracy it once was, innovations proven at the local level must scale nationally. Queenstown Lakes's 21-year track record in one of the country's most challenging housing markets demonstrates both the urgent need and the viable solution. The question is whether the nation has the political will to learn from this success before more working families are priced out of the communities they sustain.