[00:00:05]

Bernard, thank you so much for taking time to come talk to us today, I really appreciate it and we deeply appreciate the work you do with the kaka. Oh, thank you, yeah, I have fun gathering the information and getting it out there and hopefully it's useful to someone. Super. I thought I'd start off today talking with you at a reasonably high level around things like housing, cost of living, health, jobs, and maybe some of the connections that we're seeing play out right now in the New Zealand context. Could you give us a little bit of a summary from your perspective? on what you're seeing in the political economy play out at the moment?

[00:00:47]

Yeah, I have this housing theory of everything, which I've come to over time and worked out that most of the problems in our economy, in our society, in our politics are linked to this horrible shortage of affordable, healthy, warm, dry homes in the right places, and health, crime, injustice, inequality, loss of hope, stress on families, lack of productivity, problems with the cost of living are almost all,

[00:01:32]

all about how much it costs to rent, and if you're lucky enough to have a deposit, how much it costs to buy and own and service the loan on a home. And it's not just tough because everyone's got it tough all around the world. It's really bad here. In fact, you could argue it's the worst here of all of the countries where they have overvalued housing, not enough housing. And we've had a perfect storm of reasons for this, but it means now that we don't really have an economy.

[00:02:06]

We don't have a normal society. We have a housing market with bits tacked on. Can we unpack that a little bit? Because our listeners and viewers may not really get the underlying structure and the history of how that has come to be. And in particular, the role of central government, the role of local government. and the role that Treasury plays in its interaction with the Reserve Bank of New Zealand around things like participation in the economy and controlling inflation and such like.

[00:02:43]

Could you help people understand a little bit more about why it's ended up the way it is? Yeah, it's worth taking everyone back in history a bit to a different era when it only cost two or three times your income to buy a home. And this was at a time not long after the 70s. So I'm talking here about the early 1980s. There was a time in New Zealand when we used to build around 12 to 15 homes per thousand people every year. Now, that was the peak in the early 1970s, but for a long time, through the 60s. 50s, 60s, 70s, New Zealand was actually really good at building lots of homes.

[00:03:27]

And it happened because the government was quite heavily involved in financing, in organising and in underwriting the building of these homes and new suburbs. Because there was a different aspiration really of government and of society actually. Got to remember, after the Second World War, through the late 40s, 50s, 60s, 70s, New Zealand saw itself as a young growing population with lots of people coming in from the rest of the world, very high birth rates, the baby burn.

[00:04:01]

And we had this history through the 50s, 60s, 70s of quite high tax rates. Now, unfortunately, a lot of those high tax rates happened because of the Second World War. When you're in government and you say to people, we need these high taxes so we can... make the weapons and buy the weapons to fight for our survival, everyone goes, you know. And so we had these high taxes, and those taxes were used to run the Ministry of Works, and that money was spent.

[00:04:33]

And no one asked for the money back. It was, we're investing this as a society, as a government, for the future, for these kids, for these families, for these men who just started families after the trauma of war, for all of these places up and down the country where there were growing small towns. You know, we had growing numbers of sheep. We were these two islands that were exporting socks off, wool, butter, meat.

[00:05:03]

Lots of butter, butter was cheap, to Britain mostly. And times were good because we got ahead of the curve of the growth in the population. The government used to plan to build suburbs and they used to work with councils to invest money in new networks of pipes, new roads, new bus services. The Ministry of Works used to plan and they used to have a long -term plan.

[00:05:33]

It didn't rely on the boom and the bust of the housing market and the government just spent the money. They didn't go to the council and say, we're not going to give you the money unless you do this. The council didn't say, we're not going to approve this unless we get money from the government. They just spent the money and they could do that because taxes were higher. and because there was this different approach. Now, come along to the early 1980s, we had an economic crisis, we had Robert Muldoon in charge, and a group of people decided we needed to have a complete revolution, if you like, in how the economy was organised, how government ran.

[00:06:13]

We decided, well those group of people decided, in the late 80s, early 90s, and so I'm not just talking here about politicians, I'm talking about officials, the mandarins, if you like, the people who are the really, the brightest people in the room, the ones who say to the minister, actually the research, the theory, Milton Friedman, all of these things. tell us we should do this, we should remove all these restrictions, we should pull the government back from being involved in all these things, we should have a small government. So not having a government that makes up half of the economy, it should be 30 % of the economy or less.

[00:06:53]

And also the government shouldn't have lots of high debt, it should aim to have not much debt. And so that's where we really restructured the economy and aimed for that. And the aim was, and this is across parties, the aim was get the size of government down from 50 % to under 30 % and we need taxes to come down, these high income taxes, bring them down and remove a lot of these restrictions on exporting and importing, particularly importing because we need cheap imports.

[00:07:24]

And we want to deliver tax cuts. and, a couple of things happened, accidentally on purpose, that meant We never got to the point of putting in a capital gains tax. Because we had these big reforms we brought in a GST. We flattened our income taxes and the last piece of the puzzle was a capital gains tax. And in fact, it was proposed by the Labour government in 1989. In the end of 1989, the then Finance Minister Kegel said, right?

[00:07:55]

Here's the end of the reform process. We need to include this missing piece. Otherwise it's not quite kind of work. 1989. that was proposed never got through because that government was voted out and it was decided not to have a capital gains tax but also not to have subsidies for saving for pensions Because we actually had those, there were tax breaks for rich people to put money into their pensions, and this was seen as unfair, and that makes sense.

[00:08:27]

Why should rich people get a government subsidy to save when that same subsidy is not going to poor people? So that was removed. But what it meant was, we suddenly had an uneven playing field, a sort of an imbalance in all of the investments and incentives. And it happened at the same time that the government pulled back from essentially paying for a lot of the infrastructure you need for housing growth. So they stopped. Dismantled Ministry of Works.

[00:08:55]

They didn't go out of their way to plan for new pipes and new roads. And part of the reason for that was that they thought, in the late 80s, early 90s, We were going to go from being a high population growth, high birthrate country, lots of growth. It's all go, go, go. We need to invest, invest, invest for these new generations towards a flat population, mature aging population where you don't need to build new pipes because it's not new people. And we've already over -invested.

[00:09:25]

We've got too many pipes. We've got too many think big projects. We're not going to have any more of those. We need to stop having so many blinking officials with their gliding on cups of tea, stopping us from using our money. It's our money. We should spend it. We should have some fun now. We're no longer this... We're still in the 80s or are we in the... We're still in the 80s, yeah. And so there was some fun that was had.

[00:09:51]

Lots of parties, stock market boom, and then it busted. And then, of course, we had that period up through early 90s, high unemployment. And the Reserve Bank was set up and essentially decided to crunch inflation down, unfortunately by making a lot of people unemployed, including me, by the way, for a short period. And so long story short, quite a long story, but a long story short, from the early 1990s onwards, the DNA, the culture of our bureaucracies and our politicians, all these people in who wear suits and say, this is the right way to go, it is still there.

[00:10:31]

It's still deep in the heart of their brains that this is the right way to do it. So I'm talking here about the current Treasury Secretary. His formative years were during that quite exciting period of reform when they were told that this is the right thing to do. They believed it was the right thing to do. In fact, some of them believe if only they'd been able to complete it, to carry on and do the rest, we'd be so much better off. The trouble is.

[00:10:58]

We now know, it's now 30 years on and we look back at that time of welfare cuts, of investment cuts, of pulling back the state from being involved, so involved in the economy. You know, there were some good things about that. But what it meant though is that an entire generation was cast aside. They had high unemployment, there was a lot of disruption, particularly in the regions. A lot of people had to move. You had to move from small towns to the cities for jobs. They lost connections with their whanau, their iwi.

[00:11:32]

There was a lot of pain. And that is now residing, festering, and struggling in our biggest cities. And not just the biggest cities, you know, the Rotorua's, the Hastings, you know, the Kinspins of the world, they are really struggling, and they are cities, because of these changes. It's now. We're now at a point where we shouldn't have had too many problems if our population hadn't grown.

[00:12:03]

But this is the real issue here. From the early 1990s onwards, we didn't have that much population. But then come 2002 -3, a bunch of politicians worked out, and there was a lot of people in business who thought this would be a good idea too, that we could grow by growing our population. We could bring in lots of workers. They seemed very keen to come and work for us. All these Indian students, people from China, people from the Philippines, they're great people. They're working hard. They want to build their families.

[00:12:34]

Fantastic. And they seemed to want to work quite cheap. This is great. They don't seem too worried about the eight -hour day. So we had this extraordinary period of population growth, and you could argue it's still going on, the fastest population growth in the developed world in the last 20 years. And, we did it without having built the infrastructure for it. And now we see it in this extraordinarily high cost of housing, poor quality of housing, high amounts of homelessness, incredible stress on cost of living for poorer people, particularly if they're renting, because rents have risen faster than wages. Our housing supply has risen much slower than our population.

[00:13:19]

And, you know how I said at the start, way back in the 70s, 60s, 70s, we were building more than 10 houses per 1,000 population. We can barely get to four or five now. And this is because both councils and governments are still stuck in this idea that we have to keep debt low, we have to keep the size of governments low. And that it can be done, we can have the health system, we can have the economy, we can have the education system, and it can all be done, if only we just stretch a bit harder, we squeeze the lemon a bit more, we do things more efficiently.

[00:13:57]

But we've squeezed the lemon as much as we can, and we now know it doesn't work. We have to invest, we have to use our resources, and that may mean higher taxes, that may mean investing public money in infrastructure for housing, water, roads, schools obviously, hospitals, bus networks, rail networks.

[00:14:26]

Turns out actually that Mixed economies, capitalist economies, work best when the government invests heavily in a lot of the infrastructure and makes sure there are healthy, happy workers, well -educated and able to grow productivity. That's not happening anymore. Bernard, from a community housing perspective, we're very staunch in terms of how we define and it relates directly and proportionally to a household's income.

[00:14:59]

It's not a discount off market or something else because the New Zealand context, as you'll understand, that's still unrealistic for many, many families and we've had some research just land in the last week. on low and moderate income households, and there's nearly 200,000 households now in New Zealand who are experiencing rental stress, which means that they're paying 40 or 50 percent of their total combined household income on their rent.

[00:15:29]

Rebecca McPhee some time ago wrote a great piece for North and South called The Great Divide, and what she was speaking to there was the growing divide between those people who own property and those who don't. I'm interested to hear your reflections on where all the money's going at the moment because the word in Wellington is there is no money. You've spoken to that partially with your response around the 30 % versus the 50 % of the government's participation in the economy, in the real economy.

[00:16:04]

Can you talk me through recent history in terms of the billions of dollars that the banks are lending for the past few years? Is that going into the productive economy where people get employed and have jobs and pay rises, or is something else going on here in New Zealand? Over the last 20 years, our banks have become very efficient and successful and profitable at lending money to people to buy each other's houses.

[00:16:36]

Now, often it's been linked to first home buyers to get into the market, but more often than that, about 60 % of the lending in the last decade or so has gone to rental property investors buying up more rental properties. So they've got their own home, they might have had one or two rental properties. That lending has gone to allow them to buy the fourth or the fifth. And there are a small number of rental property investors who've got 100, 200.

[00:17:04]

And the theory is that for these people who are buying the second or third or fourth rental property, that they can make money from the capital gains on the leveraged investment. So it's really important to understand the power of leverage here if you're an investor. So let's say I've got my home, it's worth half a million dollars, I've paid off the mortgage. So I've got equity of half a million.

[00:17:35]

But the value of the home's gone up from $100,000 when I bought it 10 years ago to $500,000. So that's five times the investment returns for that money, $400,000. So that's pretty good. $4 for every dollar I put in. But let's say I'm able to, now that I've paid off that mortgage, I've got $500,000 of equity, let's say I'm able to take out a couple of hundred thousand dollars from that $500,000.

[00:18:04]

So I get a loan or a couple of loans from a bunch of banks and I buy a couple of houses. So I buy a house with a deposit of $100,000, another house with a deposit of another $100,000, and then I get some loans on top of that. And then the house price, let's say it doubles again in the next five years, 10 years, which actually is the history of house prices in New Zealand. And suddenly that house which I might have bought for 500,000 is now worth a million.

[00:18:32]

So I put in 100,000 and now I've got a million. So I went, I've made $9 for every dollar and I paid the lowest possible mortgage And I got the tenants to pay for the interest on my loan. And I was able to claim back the interest on the loan against my taxes. So I didn't pay that much in tax from all of the rent. And then, let's say I'm heading for retirement, I'm in my 60s now, I've built up this property portfolio, four or five houses, and now I want to have a good time, go away and have some holidays.

[00:19:10]

Maybe I want to help my own kids get into their home. What do I do? Well, I sell one or two of the houses for a million dollars each, and I don't pay a cent of tax, no capital gains tax on that. So let's say I put in $200,000, I get back $2 million. That is way, way better than anything else I could have put my money into. So we've had enough experience now so that people know this is how New Zealand works.

[00:19:39]

And so let's say I'm in my 30s or 40s, I'm a successful business person, or maybe I'm a successful tradie. and I want to start my own business or I've got a great new idea for a product or an export or something, or maybe I want to expand my farm, or I want to employ some new people and build a new machine or become more efficient, be better at my business, and I have a choice. I've got some spare money.

[00:20:06]

I could put that money into my business, but I know that I'm going to have to pay and I'm going to have to employ people, I'm going to pay GST whenever I buy the new machine or the new thing. I realise that adjusting for risk, remember how risky is buying this house? Is it going to go up and down like a share price? Is it going to go up 50 % one day and down 40 % the next day? What am I going to do with my spare money?

[00:20:35]

I'm going to put it into more residential property. And that is the fundamental driver now in our economy to the point where in the last four years our banks have lent all of the new money they've created, all of it, to the housing market, to owner -occupiers, first -home buyers, and mostly rental property investors. All of their new lending has gone into residential property. What about industry and farmers and...

[00:21:05]

Net zero. So businesses, they've worked it out too. Why would you put money into your own business when you can use your spare money and buy rental property, particularly when it's difficult to expand your business, it's hard to get workers, they're expensive. Let's say you wanted to build some new houses or build a new commercial building, it's difficult because the council says no, or it takes a long time to get a resource consent and time is money.

[00:21:35]

And so you think, well, I'll just buy another house that already exists. It's much easier. It's liquid. I can sell it. It's easy. Everyone seems to want to lend me money for this. When I go to my bank and say, hey, I've got this great idea for a new business, would you lend me some money? Or more importantly, lend money to the company I've created to build this. And the bank goes, nice idea. But no, I don't do that lending anymore. I only lend to people with a mortgage. Perhaps you'd like to take out a mortgage on your house to start this new business.

[00:22:05]

And so that's the other. corrosive and perverse thing about this, everything, everything comes back to the house. Everything comes back to that as an investment choice, as the driver of your personal wealth, as the reason or the reason for your status. The place where you live is where you send your kids to school. You know, the whole, you know, grammar zone thing.

[00:22:31]

As the value of property has often moved and become attached to school zones, you define yourself and your community by where you live and which school zone you're in. Because not only does it make you richer, you know, there might be a $200,000 or $300,000 premium for living in the grammar zone, but you're in the club with the other rich people. Now, there's something about humans we like to organise ourselves in groups we find simpatico with and lately that means the rich people.

[00:23:04]

Where do the rich people live? Where do they send their kids to? This is a class -based way of seeing the world. I mean, I'm 58, I'm not familiar with that. When I grew up, everyone felt the same, because they might own a house or they rent but they weren't that much richer than each other. But now they are. Now people, anyone who owns a home basically is a millionaire. It doesn't sound like a level playing field that you're describing here. It sounds as if there are some deep structural injustices in terms of the way that the game has been set up.

[00:23:41]

Yeah, and unfortunately... The people who have benefited from this, and there are beneficiaries, you know, the ones who've owned the home, they happened to accidentally own a home in 1995 or they got in before the things took off in 2003, or maybe their parents helped get them in in 2017. They are the ones who have benefited, so they're now rich, damn rich. You know, it's no mistake that the number of people flying around the world for days is higher than it's ever been. You know, there are some people who are really wealthy. There is a different class of people now who are wealthy, and they don't want to give it

[00:24:23]

up, you know, because to change it, to really change it, to change the... core incentive in our economy would mean, A, removing the tax -free status of the capital gains on that land. Now, there's different ways you can do this. You can have a capital gains tax, it can be a capital gains tax only on rental property. My preference actually is for a land tax on residential zone property. Because we forget, it's not just the residential property investors who are wealthy on this.

[00:24:55]

There's a lot of people who only own one home, but that home might be worth $2 million and they might have put all of their extra money into it. So instead of putting money into a new business or a new business idea, they've said, actually now if I add another deck and another third bedroom, that lifts the value of the property. And that's better. tax -free, and I get the fun of living in the third bedroom. So one of the most interesting things is a lot of our construction sector has gone away from building brand new homes, and particularly affordable homes, to building mega homes.

[00:25:31]

Because the only people who can afford to order up a new home, to go to a builder and say, right, I've got some equity, I've got a loan from the bank, I want to build a house that I want to live in, they already own homes. They're already rich. They don't want a two -bedroomed, 90 square metres, just the basics, warm, dry, but only two bedrooms. They don't want an apartment.

[00:25:57]

They want a standalone home with four bedrooms and two garages and maybe a media room for dad when he wants to get away and watch the rugby or a room for a trampoline out the back or a pool. This is the dream. When you're a builder and you're trying to work out, how do I organise myself? How do I make money here? Who's going to want to buy the house I want to build? You end up building standalone, big houses and they're not affordable.

[00:26:30]

Whereas in the 50s, 60s, 70s, most of the homes were not only underwritten by the government and not just underwritten in financial terms, but the actual building of a suburb and the the power lines and the phone lines and all that stuff you need for a house, that was all paid for by the government. Not only that, but when you wanted to build a house and you didn't want to spend money on a fancy designer or an architect or whatever, the government had luckily a precooked one in the cupboard.

[00:27:03]

They'd give it to the builder and said here's the group building scheme plan. Now nothing fancy and we all know what they look like, those Fletcher homes, the railway homes, you know the state houses of the type houses of the 50s and 60s, they all look the same. They're probably now a little bit cold and tired, but you can renovate them and they've got good bones and all of that, but they're simple and they were relatively cheap and the government gave the design to the builder and not only gave the design to the builder, said build this on spec.

[00:27:38]

You don't need to have a buyer before you start building, just build it. And if you can't sell it, we'll buy it off you. And interestingly, there are some little pushes here and there for the government to start doing that again. But this was being done on a much larger scale back then. So a lot of the risk was taken out. The point here is to say, back then, it was possible to build affordable housing. There were enough builders to do it. The government helped not just finance it, but advise it and make sure that all of the stuff underneath was done.

[00:28:11]

Since the 90s, the government has pulled back and also made it very difficult for councils to do as well to underwrite that growth. Because the theory was, government's bad at this, and by the way, our population is not going to grow anyway. I wish they'd told that to the politicians from the early 2000s onwards who said, I've got a great scheme. I'm going to boost the population with lots of low wage keen workers who will, let's face it, help fill up all the rental properties and boost the rents and drag down the wages.

[00:28:45]

And that's actually quite good for inflation. And actually, as a government, my first priority is to get mortgage rates down. Why? Because when mortgage rates fall, that's good for homeowners. The value of their property goes up and their cost of living go down. Brilliant. They get a tax -free gain on the way up and suddenly they've got some spare money. What do you do with the spare money? You buy another rental property with those low interest rates.

[00:29:12]

And so unfortunately, governments of both flavors have set themselves up for 20 years with the payoff being low mortgage rates for what they call, you know, middle New Zealand. Actually, you know, middle of New Zealand's becoming mostly top of New Zealand. And as you're, the shadow, if you like, the inverse of your 200,000 in the study who can't afford their housing, you know, there's another 200,000 at the top who have a lot of homes.

[00:29:45]

And unfortunately all of this has meant that we now have a divided, broken, sick, unproductive society, which for many young people is devoid of hope. And that's the most painful thing. And if you want to see what a country that's devoid of hope looks like. go to Auckland Airport and watch the 200 New Zealanders a day who are getting on to an A320, and they're all A320s, flying to Sydney on Melbourne or Brisbane, 200 people a day, including 18 babies.

[00:30:29]

So these are young families. Maybe a young family with some skills, maybe there's a nurse, maybe there's a builder, maybe there's a driver. They had given up on the New Zealand dream because maybe their parents weren't able to give them the deposit to get into the house, and now they've realised if they stay there, their costs of living are so high after they've paid the rent that they're not going to get ahead, and they're never going to be able to buy a house because prices are so crazy high.

[00:30:56]

At least if they go to Australia, A, they're going to get compulsory pensions, and B, they're going to have some spare money after their costs to be able to save maybe for a deposit. And actually in parts of Australia, and this is a different story to maybe 10 years ago, parts of Australia, they are building a lot of houses now. You go to parts of Queensland, Victoria, particularly in Melbourne, there are lots of apartments for sale.

[00:31:24]

There are lots of houses for sale, and lo and behold, housing costs are falling. And we've seen it ourselves too in New Zealand, where in some cases, few little gains here and there, like the Auckland Unitary Plan, which allowed a lot more building in some places, not all places, not as much as it should have been, but there, we've actually seen rents. rise by not as much as in other parts of the country where that didn't happen. So we do know that building lots of houses will help solve the problem.

[00:31:56]

So there's a cumulative deficit from what we've observed which sort of started and kicked in with the reforms of the late 80s and early 90s in terms of, and I've had this conversation with the Minister of Housing on a number of occasions, that there was a proactive government commissioning and enabling of the production at scale of lower quartile affordable housing. And then it pretty much fell off a cliff with those reforms. And so now we've got a cumulative deficit that's running into 30, 30, nearly 40 years of undersupply of affordable housing if you're defining affordable as lower quartile by value.

[00:32:39]

And that's different to what we'd had in the 40s, 50s, 60s, 70s, and even in parts of the 80s. We all forget that that fourth Labour government did do some house building as well. But with that 1991 mother of all budgets, and I see that as a pivot point in our political and financial history, the 1991 mother of all budgets wrecked so much and helped shift things in a permanent way that was worse, that we still haven't recovered from.

[00:33:11]

The shadows, the echoes of that are playing out in courtrooms and hospitals and on Marai all around the country. It's awful and it unfortunately is very persistent. It has woven itself into the fabric of our, what I call our political, economic, social DNA, and that is the laws. and the way our bureaucracies operate.

[00:33:40]

So it means that when a minister thinks about a problem and says to their officials or says to their mates in the party or whoever they contact, how are we going to solve this problem of unaffordable housing? The one thing which would actually completely change the conversation, the one thing that actually worked in the 40s, 50s, 60s and 70s, which was to use the scale of the Crown's balance sheet to borrow money and to use the Crown's much longer term horizons, not have to worry about profits in the next 15 months or whatever, not have to pay the high capital of being a privately

[00:34:25]

owned business. Use that balance sheet strength of our water. You know, this is two bloody big islands that produces a lot with five million fantastic people who are going to be alive for decades and decades. That essentially is the wealth that as a government you can depend on because you can tax it. You're the only organisation, people in the country who can tax that. And that gives you a special privilege.

[00:34:53]

And that special privilege, frankly, is to be able to borrow cheaply. But we have held ourselves back from using that special privilege because we thought it was dangerous. Now, it was dangerous on the hands of Robert Muldoon because he used it in a particular way. But we actually can use it now in a much healthier, much safer, much less risky and volatile way than Muldoon did. But unfortunately, the thinking of the people making the recommendations is.

[00:35:22]

Rule number one, it's a bit like the Monty Python sketch, rule number one, never borrow to solve this problem because that is something we don't do anymore because it's very bad. And I remember the days in 1984 when we were so broke that our diplomats had to use their credit cards to pay for things. There's no evidence for that. No, exactly. It's apocryphal. Yes. But, you know, things were more serious back then.

[00:35:50]

I wouldn't say it was completely catastrophic, but it was more serious, much more serious than now. And I can reel off a bunch of stats. You know, our net debt, particularly if you take into account our superfund, which is a government asset, very liquid asset. After you include the New Zealand Superfund, we have barely any net debt. In fact, our net interest costs after you take into account the dividends and the interest coming into various government assets and entities, it's so low, it's like less than $2 billion for a government that can make revenue of $145 billion a year.

[00:36:33]

So we are restraining ourselves from borrowing when our net interest costs are less than half of 1 % of our revenue. If you went to the bank and said, please sir, or madam. I would like to borrow an amount of money that's going to cost me less than 1 % of my income. They'd go... Bite your hand off. Yeah. And this is the thing. I can go to a bank if I've got some equity and a regular income, and I can borrow three, four, five, six, in some cases seven times income and be able to service debt with 30 % of my disposable income.

[00:37:18]

So we're talking about some deeply held philosophical positions and mental models and beliefs that seem to permeate across the whole political divide there. It's interesting, one of our earlier interviews was with Ganesh Nainar before he finished and the Productivity Commission was shut down and he recalled a conversation he'd had on a plane one day with Jim Bulger. And Jim turned to Ganesh and said, they sold me a dummy, didn't they?

[00:37:45]

And Ganesh said, yeah, I'm sorry to tell you, but they really did. And he was talking about this very point around the perception of the role of government as a participant in the housing market. Essentially, when you create a crisis, and you create a crisis mentality, people, humans are not very good in crises. They tend to go back to their lizard brains, you know, they panic.

[00:38:13]

They, someone says, do this. And because you've got the whole, you know, fight or flight thing going on, you do it. We were threatened in 1991 with a two notch downgrade in our credit rating. In an emergency way, Graham Scott, the then Treasury Secretary, and... Ruth Richardson flew at the beginning of 1991, flew to New York, basically went on her hands and knees in front of Standard & Poor's and said, please, please tell us what we have to do to avoid this double -notch downgrade.

[00:38:49]

This felt like it was an existential crisis. When they came back, they said, this is a crisis. We have to do something extraordinary. We have to tell people this is for their own good, that we did otherwise. And the thing we're going to do is we're going to cut spending on welfare. We're going to cut spending on new housing. We're going to cut spending wherever we can, because we know, they felt in 1991, that if they had that double -notch downgrade, interest costs would go up and that would tip the economy back into a recession that really had lasted years and we couldn't get out of.

[00:39:27]

And so everyone in the political environment, and I'm not just talking national, I'm talking labour. But lead that to their bones and still do. If I went to Grant Robertson or Jacinda Ardern or rest in peace Michael Cullen and Alan Clark and said to them, do you think it's a good idea to have less government debt and to be running a surplus or at least be in balance, they would all say yes. Because that's what they grew up with as their core belief. And it's a bit like the stories you tell each other around the campfires, about the bad old days or that time when I almost got eaten by the lion, and the thing you never do is...

[00:40:14]

put your hand up and wave at the line. Don't do that or you'll die. And everyone believes that and they remember it and it's seared into their memory. And right now, the head of our Treasury believes that in his bones. Nicola Willis believes that in her bones. Why? Because she learned her business at the shoulder of Bill English, who believes that in his bones. He was in and around Parliament in the Beehive and Government in the early 1990s.

[00:40:43]

That is the underlying belief. And it's really tragic because our world has moved on since that in a whole bunch of ways. A, we paid off a lot of debt. Our government and our economy continue to grow. And one of the sort of frustrating and painful things is that the current government. so believes in these things. We must get back into surplus.

[00:41:13]

We must start repaying our debt. We must get mortgage rates low. That's the most important thing. Even more important than building houses for our friends and family and our future. God knows why they think that because actually praying before that God, that God of we must be in surplus, we must reduce the debt, actually wrecked a generation's future, created huge liabilities for the crown. If you're looking at it in a purely financial sense, huge liabilities which aren't priced in our balance sheet, which aren't recognised if you're a company.

[00:41:49]

If you had, as a company, not invested in your infrastructure, your buildings, your roads, let's say you're a company and you decide, hmm, I'm going to make big profits this year, I'm going to take a lot of dividends out, and the way I'm going to do that is not invest in fixing the roof or repairing the potholes in the road. Now what an accountant and an auditor would do is look at that and go, right, what you've done is you've put off maintenance spending, you've put off reinvestment, and that means you now have a liability.

[00:42:21]

We know that in four years time, when that roof starts to really rust out, either you're going to have this horrible flood and destroy the rest of the building, or you're going to have to re -roof it. So that cost is still there and we're going to put it in your balance sheet. So what appears to be a big profit this year is actually just a debt in future years and unfortunately that debt, and those debts include our rising rates of mental health problems, our rising problems with diabetes, all sorts of preventable diseases, not to mention the awfulness of kids living in cold damp mouldy homes with parents who are stressed out because they work three jobs and still can't pay the rent

[00:43:05]

or the hour bill, what that's doing to their futures. Are they going to turn up in hospital with a mental health problem in 10 years time? Much more likely now. Are they going to fall along the wayside, have all sorts of stress and issues which means maybe they commit a crime and have to end up in prison? Unfortunately our government is building some things at the moment. They're building prisons and when you look at the cost of it, we're talking about a thousand dollars a night.

[00:43:37]

Or let's say you become diabetic because you can't afford decent food, and you're stressed, and whatever the social issues are around becoming diabetic, suddenly you have to have your foot amputated, or you suddenly have kidney failure, or whatever. That's $1,000 a night, night after night after night, so there's a cost, there's a liability in future, it's just not properly priced.

[00:44:04]

So the point I'm trying to make here is that you can only do that, not reinvest, cut back, bank the dividends in the form of tax cuts for so long, and then the cost will come. And unfortunately, it's coming now, and it will come in the future, and it's a mistake to think that we can. Do what we did in the last 20 or 30 years, which is cut, cut, cut, reduce, reduce, reduce government spending, spend, spend, spend, make big profits and tax -free capital gains and everything can carry on.

[00:44:43]

No, you will have to pay for those hospital bills. You will have to build those new prisons. You will have to walk down the street and wonder why is that person sleeping in the front, in front of the shops? Why is that person lying on a cardboard box?

[00:45:08]

What's happening here? Well, we know what's happening here. Collective decisions by voters, by politicians, by bureaucrats for 30 to 40 years is coming back to haunt us. Unless we change what we do. It's going to get worse. And we've actually seen how it's gotten worse in the last couple of years because the current government has pulled back even further and slammed the brakes on even more investment in infrastructure, housing, hospitals that have been delayed, roads, all of those things.

[00:45:39]

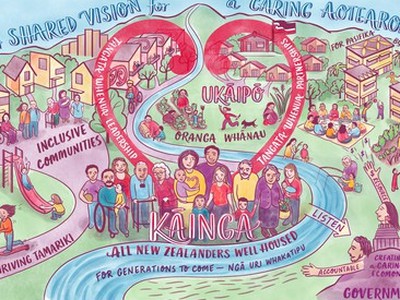

Let's flip into a conversation about how we might change the policy settings and how we might as a nation make some different choices because ultimately we've made a series of choices that have got us to the place where we sit now as a nation. And we often, as a discipline within the community housing sector, particularly We think quite deeply about the sort of place we want to live in and we want our children to live in we We're very pleasantly influenced by our many kaupapa Māori organisations who are taking hundred -year views 200 year views of things They're doing some deep long -term

[00:46:20]

thinking in a way that our political cycle often does not Think with a three -year cycle and in the short termism that you've been talking about and and so I'm interested to hear some of your thoughts around what we might do differently in terms of our funding and finance and Policy settings as they relate to the housing situation. We find ourselves in as a nation Yeah, well, there's lots of choices lots of ways you can do this and I've thought about it, too And again, I'm no politician, so I don't have to win anyone's vote But essentially, we have to change that core incentive, which has gone wrong.

[00:46:59]

That decision not to put a capital gains tax in in 1989, that decision to remove the incentives for savings and long -term business and other assets, that has to change in some fundamental way. My view is that a big part of the problem is not just rental property investors, it's owner -occupiers who are sitting on and live on and base their futures on those tax -free capital gains. We can't just be taxing the capital gains on rental properties, it has to be on the individual's home, because that $1.64 trillion, that's the value of our residential property market, is now worth almost four times our GDP.

[00:47:40]

That is twice as overvalued as the housing markets in the United States and in Australia. It's also worth... 20 times the value of our stock market. And in the United States and Australia, the housing market and the stock market are around about the same value. So if we're going to change those incentives, so instead of investing just in buying each other's houses, we invest in businesses and training and skills in health so that people are going to go to work and be happy and healthy and productive.

[00:48:15]

Actually growing the happiness of the country, then we have to change that core incentive. That's right at the heart of it. I don't think we actually achieve much with, for example, a capital gains tax on rental properties alone or a capital gains tax on all businesses. That may actually discourage some people from trying to build wealth in businesses. I actually think it's a good idea to build wealth in businesses. We also have to. just discard this idea that we can make it all work with a government that's worth 30 % of GDP.

[00:48:49]

That's just not possible with an aging population, with the new technologies that we have in health, which are more expensive, you know. 30 years ago, I couldn't get a knee replacement with the fancy titanium. I couldn't get a, you know, a piece of DNA engineered treatment for my cancer. That wasn't there. It is there now. I want it. I need it. I expect it. I can get it if I live in Australia. Can't get it here.

[00:49:19]

We cannot have a modern, reasonably stable, productive, happy society with a government at 30 % of GDP. We need to abandon this mantra, this idea that that's the right level. It's not. It's not anymore. You could argue it was never right in 1991 either. We need to use the Crown's balance sheet and its ability to tax in its long -term Its long -term its long -term ability to Use the resources of the country and to tax those resources and also the long -term Liability of having to deal with the problems if

[00:50:00]

we don't fix them it's the state which has this privilege and this power and this asset and While we still have a democratic State where you know the crown Is the central organising force in our society the one that sets our laws We should use it. We should use that exorbitant privilege too. For example, let's say we and my preference is for a land tax on Residential zoned land so not the buildings the land And that includes land that's not built on.

[00:50:37]

So there's a whole bunch of sections out there with pipes underneath them and roads, and they're not being built on. Why? Because if you're a land banker, A, you've made your tax -free capital gains, it's actually a pain in the arse to build a house that's expensive. You just wait for the next rise in land prices and away you go. In fact, you're probably better off just selling the land to some mug developer who thinks they can make money out of it. The real money is in the land banking. So A, you tax that.

[00:51:06]

And I think actually you tax it at a high level than an actually occupied home on that land. And what that does is immediately change the incentives. That says, if you've got some bare land, you'd better build a house on it because it's going to cost you more to have it. So there's a real opportunity with all of the RMA reform that's going on, for example, right now. To have a look at that. Yeah, because then you can use the money from that land tax I'd call it an infrastructure and housing affordability levy myself. But anyway levy catch movie, whatever And I actually think you do do it at let's say 0

[00:51:47]

.5 percent of the value of the land Her random basis right? Yeah, and if you're a Nana and you're living on a section I'm when you wear it and a former state house in the lands with 10 million and the building's worth $100,000 and you can't afford 0.5 percent of 10 million Fair enough. We're not going to make you pay this year. It'll get stacked up as a as a something you pay Unfortunately when your estate settles up We may not even charge interest on it, or much interest, but that's how we get around this problem of, you know, actually it's a problem for a lot of councils too, you know, people who are rich but cash

[00:52:30]

poor. And that money gets set aside for the government and for councils. And you say to the councils, actually we now have a new revenue source to back the borrowing that both we as the government and you as the council are going to do to pay for these railways and schools and footpaths and playing fields and pipes and all the things you need for a bunch of houses. And of course, the more houses you've got on the smallest amount of land. the less proportionate land tax you have to pay.

[00:53:05]

So what it does is it incentivises denser development and makes you think about ways in which you can build your city, because really that's where we need to be building the houses, in the cities, and in the cities, close to the city centres, close to transport hubs, close to... Social infrastructure. Absolutely. You want to be able to have a one, two, three, four -bedroomed apartment or whatever it is that's close to a train station, that you can literally live a good productive life, go to the school, go to the university, go to your job, go to the church, on your bike or on the bus or whatever it is, and not necessarily have to have a car.

[00:53:47]

Now if you're rich and you want to do lots of driving around the country, yes you'll have one. But... We need to restructure where we live and how we live in a way that means, you know, we have warm dry affordable apartments. We can build them. They are being built now. Now, we haven't been very good at it in the past and we haven't done it in volume, but a lot of the incentives in the past and now are not there. The incentives are for builders to do standalone four -bedroom, two -carriage, seven -bathroom or whatever houses.

[00:54:21]

They're not there to build apartments. Why? Because when you build, let's say, 20 apartments on one section, it's four stories high, you know, that's a lot of engineering work. That's a big resource set. That's some ground work. That's maybe I need a lift. You know, it's starting to get expensive now. Why don't I just build three townhouses on that section? You know, I can flip the townhouses for three million bucks each. I've made the money on the land. I've housed three families. Good.

[00:54:51]

Well, just imagine if you could house 20 families, and that land value, which by the way would go up, and you'd make your tax -free capital gain, because there's no capital gains tax still. What I'm saying is we should have a land tax instead of a capital gains tax. And that means that when you build a business and it's successful, and you sell it, you make a capital gain, it's tax -free. So what you're doing is flipping the incentives from being all about investing in leveraged residential land, to investing in businesses and business ideas, and in lots of new houses on small amounts of land.

[00:55:32]

And building houses on land, that's already been put aside for housing. They sound like strongly aligned policy initiatives with going for growth and stimulating the New Zealand economy. They sound perfectly reasonable and palatable. What are the barriers? do you feel to getting this sort of stuff over the line? They're purely political. So let's say I'm part of the voting population, it's around about 10 to 15 percentage points worth of the voting population, who are in the middle, who flip one way or the other in election time.

[00:56:06]

They are typically older, they are typically on the edges of town, so they live on sections, what your traditional standalone family sections. They have kids, and they want their kids to live the same Kiwi dream as well. That means they don't want that equity in their house to go away. They want their kids to benefit from the same getting on the ladder escalator that they do. Do you think they're starting to notice that their kids are taking their babies and getting on airplanes and flying to Australia?

[00:56:36]

Well, this for me is the core emotional argument I would make to them. I wouldn't hit them with, I'm about to take away that juicy, tax -free, leveraged capital gain. That's not how you knock on the door and say, hi, have I got a deal for you. What you say is you knock on the door and say, hey, what have your kids said they're planning to do in the next 10 years?

[00:57:06]

Are they going to go and live in Australia? Have they asked you for a deposit yet? What do you really want in your life, Mr 55 -year -old man and 53 -year -old woman, or teenagers or kids who are just about to graduate from university? What do you really want in life? What is the thing that will make you happy?

[00:57:32]

And I know what I'd say, and I think most people are actually, people are people. They all want a happy family, their kids to be warm and safe. And even better, they want their kids to have kids. They want grandkids. They want to be able to cuddle a grandkid, show them off at the barbecue, you know, play cricket on the back lawn with them. They want that. They want their friends and family together. They want to have a celebration at the marae.

[00:58:01]

You know, when there's a big thing on, they want to come together to celebrate Nana when she's gone. They all want to be together. They want to be families together. Now, what happens when that kid goes and lives in Sydney or Melbourne? Now for a long time, there's a big chunk of New Zealand that thought, you know what, that's not that bad. You know, I go there for a holiday, go there for six weeks, spend some quality me time with the grandkids, and then come back to New Zealand.

[00:58:32]

You know, it's pretty cheap to fly across to Sydney or Melbourne, or it was in 2019. And that's why I think COVID had such a shocking effect on what I'd call rich and middle New Zealand. Suddenly, they couldn't do that. They couldn't make that work. Suddenly, they were watching their grandkids have birthday parties on Skype. Well, I know no one uses Skype anymore. Maybe two. And suddenly I realised, oh, I'm apart from my kids.

[00:58:58]

Just imagine being that 53 -year -old mum taking a phone call from their 25 -year -old daughter. She says, Mum, I can't sleep anymore. The baby's crying. Come and help. You can't just drive down the road. You can't cuddle a kid while your kid has asleep. You can't just go around to watch the rugby with you. That's gone. So what do you do? And for a lot of people, there's a really interesting number in the stats when you look at the migration stats.

[00:59:31]

Yes, there's lots of 20 -somethings, 30 -somethings with kids who are gone. And then there's this eco -migration of people in their late 50s and early 60s who are gone. Why? They're going with their grandkids. Now, you know, hey, maybe that's what it's warm, it's dry. The medical system in Australia is better. And what's interesting is that since last year...

[00:59:58]

New Zealanders living in Australia now are proper Australians. They have all the same rights to the medical insurance, to the universities. Suddenly they're all Australians again. They're not just second class citizens. And that's one of the reasons there's been this new acceleration. And despite what politicians say about, oh, this has happened before, it's no worse than it was in 2012. Actually it is, because back then our unemployment rate was significantly higher. And now it's not just the workers who are going, it's the parents who are going.

[01:00:30]

And for me, one of the most interesting and heartbreaking stories I've read just in the last couple of weeks, is the stories of the dislocated, slightly...

[01:00:47]

surprised and lost Māori people living in Australia, the so -called mozzies, which by the way is a pejorative term which they're not thrilled about, who feel disconnected from the land, their family. And they have these 30 % of Māori live in Australia. You know, some of the most successful cultural groups, kapa haka groups, are Australian -based Māori.

[01:01:18]

And you know, there's a brokenness. I'm apart from the land. I'm apart from my history, my family. Is this what you want? And no one's asked that question yet, because they're too scared. Because they worry that someone will jump in and say, oh, well, this is a death tax. This is going to kill the Kiwi dream of getting into a home and getting rich because the land value increased. You're going to change things.

[01:01:52]

You're going to make some people poorer. Yeah, financially poorer. But they might be socially, family, future history richer. This country will then be richer, more cohesive, happier, and stronger because we're actually quite rich. And this is the thing that really gets my character when someone says, well, there's no money around. Here's a really interesting fact to it that will blow your socks off.

[01:02:21]

It blows everyone's socks off when I tell them. And a lot of people don't really understand or know it because the story of higher interest rates that we've had over the last three or four years is that it's universally bad. That there's a whole bunch of people who suddenly are poorer because they're having to pay more interest costs because they're borrowers. And fair enough, there's a lot of borrowers out there, particularly if you're young, you've got a big loan, you're trying to pay off the house, you know, you've got other costs. It's an issue. And that's why it's what you read about at the top of the paper or why the politicians are worried.

[01:02:50]

Yes, borrowers hurt when interest rates go up. But there's a bunch of people, typically older people, wealthy people, who have paid off their mortgages, who may have several homes, who have term deposits. And this story, oh, there's no money around, we're all on the bones of our bum. You know, there's just no money for that investment, there's no money for that school, there's no money for that housing complex, we just can't afford it. We're all going to have to tighten our belts because everyone's doing it tough.

[01:03:19]

Well actually, over the last three and a half years of high interest rates, household income net from savings, i.e. term deposits, versus mortgages has risen. So what often happens is that when interest rates go up, I pay out more in my interest on my mortgage. It goes to the bank and then the bank transfers that to the person who has the deposit because they have to pay a higher interest rate on the term deposit. Net -net over the last four years, more money has gone into household pockets after that because the banks have had to refinance their international borrowings with local term

[01:04:02]

deposits. There's now 250 billion dollars sitting there doing nothing in term deposits. It's great for those people who've got savings and have paid off, they don't have to worry about things. $250 billion. $250 billion is sitting in term deposits. When you asked right at the start, where did the money go? All of the COVID money, all of the borrowing, all of the spending, the tax cuts, all of that, where did it go? Eventually it just filtered down into term deposits. Now that's - Who owns those term deposits?

[01:04:33]

Rich New Zealanders. People who are older, who've paid off their mortgages, who might have rental properties, who are wealthy. Some of them are really wealthy. And we know that from some of the research that was done just before the end of the last government, the David Parker Commission from the IRD. Some people are doing really, really well, and they're not paying tax on the income they've made from their capital gains on land. Say this. sort of sparked some social justice response from me because in essence when you think about it, from a community housing perspective particularly, we have a whole range of different products and services that we offer.

[01:05:16]

And one of the really big important areas that we work, aside from affordable rentals and social housing where we play with Kainga the state provider who also do social housing, we do a lot of shared equity and progressive home ownership products because what we're trying to do is we're trying to support those families who have the aspiration and many, I would say most do. are particularly within our Pacific peoples and Māori communities.

[01:05:47]

They do not, when we generally are on the grassroots level talking with families about what their vision of their future is, they do not aspire to be a tenant in a kind or order house paying a rent. They aspire to the independence and intergenerational wealth accumulation of owning their own home or part of a home which they can pay off. And so in some ways, some of those families, as you alluded to earlier, have been renting for 30 years, but during that period if that was a mortgage they could have paid off their mortgage and they would now own mortgage free their home, yet instead what they've been doing is paying off someone else's mortgage.

[01:06:26]

And so that wealth transfer has been enormous.

[01:06:32]

We are desperately trying to do as much as we possibly can as a community housing sector and to grow the volume of what we do. We have extraordinarily low by international standards levels of social housing in New Zealand, so we're still below 4 % when most other jurisdictions within the OECD are sort of somewhere between 10 and 20%. So we've got an awfully long way to go. We stopped. Yeah, so we've got that cumulative deficit.

[01:06:57]

So just recently in Budget 25, there were some reasonably significant announcements, one of which was that the government has decided to try and level the playing field as the language of the Minister of Housing as between the community sector and the state provider Kainga Ora. And one of the mechanisms that they are using to do that is that they are providing an underwriting support for the Community Housing Funding Agency.

[01:07:24]

The Community Housing Funding Agency is really a simple replication of a structure that exists in almost every other In fact, we're one of the last countries in the world to have this financial intermediary that basically provides lower cost debt to the community sector so that they can do more affordable rentals, social housing, and especially important these progressive home ownership and shared equity products.

[01:07:51]

They went to a point and provided an underwrite which is facilitating the Community Housing Funding Agency to get a credit rating, which is great, but in almost every other jurisdiction around the world a full guarantee was provided. Are we yet again here bumping up against this mental model in Treasury that says we shall not... What's going on there? What's the problem? Because we tried this with Twyford and Robertson when he was the Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Finance and Twyford was Minister of Housing.

[01:08:24]

This is the third attempt that we have had as the community housing sector to establish this very important tool in our financial toolkit that allows us to get low -cost debt. What's the problem? Why can't they get a full guarantee, which is what is really needed to drive that cost even further down? Because people in Treasury have a foundational view that the government should be smaller. Right. They have a foundational view that the Crown's balance sheet should be absolutely and not be put at risk. by being used to guarantee someone else.

[01:08:59]

So they don't want to bind themselves or bind future governments? Yeah. And they want to make sure that the state stays as small as possible. One way to make the state bigger is to underwrite the private sector doing things. And also, they worry that there'll be one organisation that does a bad job.

[01:09:22]

Someone runs off with the money and it's embarrassing for the minister when this is exposed or whatever, that the controls won't be in place. But fundamentally, it's about not increasing the size of the Crown's balance sheet, because they believe in their bones. And I've come to this view after many, many long conversations, off the record, on the record with people who are, and we're talking 10 or 15 people, really.

[01:09:55]

The mandarins of our country of the last 30 years are a fairly small group of people. They were often quite young in their 20s, early 30s, in the late 1980s, early 1990s. One of them, Ian Rennie, is now the Treasury Secretary. Graham Scott, he's still on the, he was involved in the government's social investment. Chairs the board.

[01:10:25]

Yep, chairs the board, and he's been very influential. But there's others as well. You know, up until very recently, the likes of Mary Sherwin. brilliant, nice person, you know, Alan Bollard, John Whitehead, all of these people are from a generation which when you get them a little bit drunk, give them too many coffees and you say, what is it that's really, really, what should we never do? What should we always do?

[01:10:55]

What's the thing that is like your foundational belief? You know, it's when you talk about life, the universe, and everything with someone you say, what is it that really matters? And they say, well, you know, I believe in God, or I believe in my family, or I believe in my mother, or that's the thing that really matters to me. When you put that question to them, they say, the thing that really matters is that the government shouldn't be doing this. The government should get out of this.

[01:11:24]

The best thing we can do for future generations is to hand on to them a government with That doesn't have to make those horrible choices that we made in 1991 in a way. I get it You know if you were freaked out in 1991 the country was going to go bankrupt We'd almost just been a dictatorship five years earlier when Rob Muldoon refused to hand over the keys, you know The diplomats were having to use their credit cards.

[01:11:51]

You you start to think If I do anything in my career, it's to never be there again. And so that's their thinking Now, unfortunately what they missed out on or what they believe they believe that gliding on was real and I'm talking for those people who don't know TV series. Yeah, it's a great TV. If you go to a new film archive or NZ on film, there's it's online It'll be on YouTube somewhere.

[01:12:21]

It's this... Bureaucracy portrayed at its worst, really. Yeah, yeah. Everyone's wearing cardigans. They're all drinking cups of tea and they never do anything. And it's funny and it's brilliant. And it just appeared to nail the sort of malaise at the heart of New Zealand. But actually it wasn't true. You know, there's a generation of New Zealand bureaucrats who built this country, who built all these dams and these roads and these suburbs and people at the Ministry of Works were fricking heroes, you know, Peter Fraser and all these people, Michael Joseph Savage, they were proud to build houses. You know, they they were there to cater for families that had five kids.

[01:13:00]

You know, that's what they believed they were there for. They believed that this was a young, growing country and it was their job to build the underlying infrastructure for it, not to pull back. Anyway. The people in charge still believe that they should pull back, that it's not their role, that everyone's better off if they actually don't use the power of the state. And this is where, when you go to them and say, hey, how about underwriting this non -government organisation to build a bunch of things that will actually compete partially with the private sector, it's easy to say no.

[01:13:37]

And it's easy to say, well, it's not my problem, it's not my role to provide housing for anyone. Yet there's no evidence anywhere in the world that if you leave the housing market to the private sector, that it will ever commission affordable housing for low and moderate income households. Yeah, and any economist, and they're all economists, with their salt will know that there are market failures. And this is the most monumental, important market failure in our social and economic and political history.

[01:14:09]

It's impacting everything and everyone now. The failure to build affordable homes, small homes, warm, dry homes for people who are on moderate incomes is awful. Now a good chunk of it's land costs. It also is because we stopped being able to build affordable, cheap ones quickly. Now you can have some debates about building materials costs and size of buildings and restrictions on insulation and triple glazed building, whatever.

[01:14:42]

We're just not very good at it. Now other countries are better at it and becoming better at it. And actually there's some people in New Zealand who are starting to become quite good at it. They've worked out how to... build a home for, you know, $3,000 a square metre instead of $8,000 a square metre, and they're using techniques that the rest of the world is using, and they're doing things at scale, which is different. There aren't actually many builders in New Zealand that build things at scale. It's one of these weird markets where there are 300 participants instead of two.

[01:15:11]

And none of them have any real economies of scale or systems or workers who've been there for longer than two years. We have this weird contractor -based boom bust. No one's really sure about anything. They're all bumping into each other when they do work. When there's no work, they're all jumping on planes to Australia. It's completely dysfunctional and inefficient. And unfortunately, it's holding back the entire economy. We need a few really large... builders, doing projects with 100 apartments, 200 apartments, big new areas, you know, let's take that old railway yard and

[01:15:52]

put a thousand houses on it with some great parks and, you know, connections to public transport and all that stuff, and that's complicated. It requires balance sheets, it requires planning, it requires a workforce that are going to after next, not, hmm, that apprentice might decide to blast off to Australia to be with his girlfriend. I'm not sure if I should commit myself to that business if they're not going to be there. Do I have the balance sheet for that?

[01:16:20]

Why would I invest in the new technology that's needed or the training to be ready in two years for that apartment building when it comes? What I should really do is use any spare money I've got now to buy an existing house to make the tax -free capital gains on the leverage land. So this is the basic problem. Around we go. And so that's why we need things to be done at scale with the power of that balance sheet.

[01:16:49]

Now it doesn't have to be the crown that is the only one able to use that balance sheet. And as you say, all around the world, America for God's sake. Has anyone heard of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac and all this stuff? Australia, you know, they've started to get it right with their authority, which is, you know, doing the borrowing on behalf of community housing groups. Britain done this for many, many years. Housing Finance Corporation. This is not radical.

[01:17:19]

This is not Marxism. This is not, you know, some sort of weird thing. This is something that works in other places. Donald Trump would never think of dispending Danny May and Freddie Mac or destroying the idea that the US mortgage is actually based on a subsidy from the government, which is the ability to raise debt for 30 years.

[01:17:46]

What we should have is a vibrant, strong use of the Crown's balance sheet to provide the finance for the Crown and for other parties who we trust. We're not just giving it away to every Tom, Dick and Harry. Someone's going to check your finances and understand who you are and you're probably in a non -profit and we know where you live and if push comes to shove we can probably get it back in some way. And if you're using it to build a house, well that's great because then if you've got someone who owns their own home and builds their family and is stable and their kids, doesn't bouncing through five schools in three years.

[01:18:24]

That kid is going to be healthy and productive and not turn up in prison. You've reduced your liability. And this is where I think the Treasury should take a different view, which is there is a Crown balance sheet. It is an exorbitant privilege. It lasts for decades and decades. There are undescribed, unmeasured liabilities on the other side of that balance sheet in future. How about you reduce some of those by using the balance sheet now to help those people who perhaps are more connected, perhaps have already had a good start, and are doing more than just building houses.

[01:19:01]

They're helping people with all the other things they need to get into the house and stay in the house. And there can be lots of different flavours. You've got progressive ownership, you've got the shared equity, you've got the There's lots of horses for courses. Maybe the old Kainga Ora model, yeah, it's not the only thing. Maybe you can do both. You should do both, actually. Yeah, a blend is always what we'd be advocating for.

[01:19:30]

There are some places in the country where it's best that Kainga Ora do their thing, and there are many places across the country where providers, community -based local providers are going to do the best, and there's often a blend of the two. And if you talk to any economist or fund manager or anyone who thinks about how assets work, returns on assets, the one thing they'll say to you is diversification. Yeah, absolutely. How do you reduce risk? How do you make sure that you get, over the long run, a good return?

[01:20:01]

Diversify! This is the best way to do it. Well, we're fabulously diverse. There's over 100 housing providers across the country from Invercargill to Kaitaia and everywhere in between. Speaking about risk. I just want to ask you, I was talking last week with the chief executive of a large community housing provider in Northern Rivers, which is on the east coast of Australia. And they had a really significant flood event, which wiped out 5,000 homes in their region.

[01:20:31]

And here we are 2025 and they're still recovering. They have acute and chronic homelessness, which still endures after many years of trying to build their way out of what was a 1 in 200 year weather event. We're thinking a lot about engineered resilience, managed retreat and climate risk as housing providers around the country.

[01:21:00]

Just even in the last few weeks, there have been two 1 in 100 year events in the Nelson -Tasman area. In three weeks, yeah. What are your thoughts in terms of what the future looks like, and dare we mention the words climate change? Well, you can choose not to, but it's in every story that ever matters right now. I was looking at a news bulletin a couple of nights ago. You know, you watch, well I do anyway because I'm a news junkie, from start to finish.

[01:21:33]

And you look at the 17 stories that were there. And there's sports stories and there's political stories and there's crime stories and whatever. And of the 12 stories, nine of them were either involved with, caused by, affected by, about climate change. But almost none of them had mentioned the word climate change. So you know all these weather events? The one growth area media right now is covering weather events. And we know because climate change makes these events more extreme and more frequent, it's going to happen.

[01:22:05]

So what do we do about it? Do we? prepare? Do we ensure that the most vulnerable don't get done over? You know, when there's a horrible event, they're living in a caravan in a caravan park right next to the river, and their caravan gets washed away. What happens then? You know, do we have a home for them? What's going to happen to them? You know, maybe they're getting on a bit, they're old, maybe they've got a wheelchair, maybe they need some regular treatment. Do we have a home that's in good shape for them?

[01:22:39]

What happens when, you know, maybe they were regularly taking their medicine because they were in a nice stable place, and they had family around them, and suddenly they had to move to another part of the country, and they don't have that support, or their lives are disrupted, and they can't afford to drive the car half an hour to the chemist and pay the five bucks for the whatever, and so they miss their medication. Well, you know, they're in hospital, a thousand bucks a night. So there's actually an opportunity here to get ahead of the curve.

[01:23:09]

Instead of selling all the bits of land next to the river and beach, because that's what you do when you make money out of leveraged tax -free gains on capital gains, you get as much land as you can, you cut it up into sections, don't need to build on it, just get that section, and then you make your money, right? So it's all about getting the land rezoned for residential and then moving on.

[01:23:39]

So you go to the council and you say, yeah, I know it's a bit of a flood risk, but, you know, we've got a housing problem. We need to zone these for residential. So what we have at the moment is in Auckland, our fastest growing city, a good percentage of the consents in the last two or three years were on floodplains. So what do we do? We build lots and lots of houses in places we know aren't going to flood, where it's unproperly.

[01:24:06]

You know, we've got hundreds and hundreds of homes, warm, dry, concrete, away from the rivers, away from the beaches, not vulnerable to storms, can cope with some rain and some wind, lots of nice parks and things around there, close to the bus stations, all of that. But that's not something a private developer or a single person or a single family can do. You can't rock up and say, right, I've got I've got enough money to build a hundred homes.

[01:24:37]

What you need is organisations with balance sheets, with people, with structures, cultures, connections that are going to last longer than whoever is the head of the family or whoever's got the job that supports that line. It can't be just one line. It has to be bigger. It has to be. like the rest of the world, where they use the power of the Crowns, well they don't call it the Crown of the United States, but the Republic's balance sheet to help build things.

[01:25:09]

And you're talking there about a planning, a long -term planning instrument. Planning's not flavor of the month at the moment with the current Minister of Housing. It's a pity, because you know what, go to Singapore, go to China, the places that are the demonstrably most successful economies in the world right now. Singapore's a really good example, because it's a mixed economy. It is democratic.

[01:25:39]

Pretty democratic. It is a place where the foundation of everything, of their growth, of their education system, their ability to train up to be high -tech, high -skilled, high -productivity, everything is about the planning to make sure everyone has an HDB flat. Now you may not still be living in that HDB flat after you've got your degree and you've started your family, maybe you move into the fancy condo apartment. That's fine, but you had that base.

[01:26:09]

You knew you were going to live there. You formed communities. You knew about the Hawker Centre underneath. You got the cheap chicken meal every day. There were schools connected next by, which the state sure as heck made sure you went to, and you know what? That's a productive, prosperous society. They planned things decades in advance, and this is not a bunch of communists.

[01:26:36]