Over the past three decades, New Zealand has witnessed a profound transformation in its housing landscape. Historically celebrated as a model of equitable home ownership, the nation now finds itself entrenched in a housing crisis characterised by stark inequalities, affordability pressures, and a growing divide between asset-rich homeowners and asset-poor renters.

Central to understanding the current predicament, and charting a path forward, is a comprehensive grasp of the historical shifts in housing policy and their implications on social equity.

The post-war housing model: successes and lessons

In recent submissions to the Waitangi Tribunal, extensive historical analysis demonstrated that post-war New Zealand established one of the most robust and enviable housing policies globally, integral to the broader welfare state structure. Home ownership formed the cornerstone of this policy, significantly bolstered by state interventions designed explicitly to facilitate widespread access.

This era, underpinned by visionary leadership such as Michael Joseph Savage and later Sid Holland, was characterised by intentional strategies aimed at home ownership, offering favourable mortgage terms and innovative financial supports, such as the capitalisation of family benefits as deposits. Indeed, at its peak, government subsidies accounted for nearly 30% of the cost of an average home.

The shift from public to private

However, the housing landscape shifted dramatically from the late 1980s onwards, particularly in 1991, when a radical policy pivot occurred under the then National government.

The sale of $2.4 billion in state-owned mortgages to the private sector signalled not merely a financial divestment but a fundamental ideological shift away from state-supported home ownership toward reliance on the private housing market. This transition proved catastrophic in retrospect, severely limiting home ownership opportunities, especially for lower-income and historically marginalised communities, including Māori and Pacific peoples.

Rising inequality and housing unaffordability

As state involvement diminished, private sector dynamics became increasingly dominant. Rental markets expanded rapidly, driven by speculative investment and profit motives rather than community welfare or social stability.

Consequently, the affordability and security previously associated with home ownership was severely compromised. Rental inflation consistently outpaced income growth, pushing a considerable proportion of the population into precarious financial situations, where housing costs routinely exceed internationally recognised affordability thresholds of 30% of household income.

Current international metrics reveal New Zealand's housing cost-to-income ratio sits alarmingly between seven to eight times the median income, significantly beyond the recommended affordability ratio of three.

Impacts of asset inequality: economic vulnerability and social costs

This shift has created not only immediate financial hardship but also structural inequalities with profound long-term implications. New Zealand is now witnessing the solidification of a divided society, approximately 60% with property assets and 40% without, effectively establishing an entrenched class of asset-poor citizens.

This scenario disproportionately affects Māori, Pacific peoples, and lower-income Europeans, exacerbating socio-economic disparities and limiting intergenerational wealth transfer opportunities.

The lack of adequate housing assets among this significant segment of the population imparts severe vulnerabilities during economic shocks, such as the recent COVID-19 pandemic. Homeowners were able to negotiate mortgage holidays and financial leniency, preserving their financial stability.

Conversely, renters had little recourse, with negligible rental relief, perpetuating cycles of economic instability and hardship. Additionally, extensive research demonstrates that home ownership correlates positively with better health outcomes, educational achievements, reduced welfare dependence, and lower crime rates — benefits that persist even when controlling for income and educational differences.

Reviving home ownership: the role of progressive financial models

Addressing these entrenched challenges demands a return to policy strategies that prioritise home ownership and financial inclusion. Importantly, this is not merely about reviving historical models verbatim but re-envisioning them within contemporary economic realities.

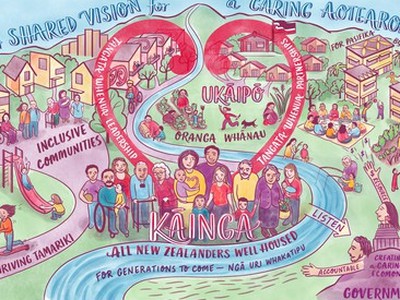

Progressive home ownership and shared equity schemes stand out as pivotal financial models capable of bridging affordability gaps. Community Housing Providers (CHPs), given their localised presence and non-profit status, are uniquely positioned to deliver these models effectively.

International examples from the United Kingdom and United States highlight how CHPs successfully provide mixed-tenure housing solutions, combining rental options with pathways toward ownership through shared equity and rent-to-buy schemes.

Strengthening community housing providers

New Zealand's community housing sector, despite its potential, currently faces structural and financial challenges that limit its effectiveness.

Recent government initiatives, such as the Community Housing Funding Agency, offer promising avenues by facilitating lower-cost financing for CHPs, enabling them to compete with larger state entities like Kāinga Ora. Yet, such initiatives remain insufficient in isolation. They must be accompanied by robust state incentives comparable to those historically offered for home ownership.

Inclusionary housing and legislative reform

Furthermore, current reliance on Income-Related Rent Subsidies (IRRS) has inadvertently skewed the sector toward rental provision, undermining CHPs' ability to deliver diversified tenure models.

While IRRS effectively supports immediate housing affordability, it paradoxically creates disincentives for improving one's socio-economic circumstances, as increased income often leads to eviction from subsidised housing. This policy contradiction perpetuates dependency rather than fostering independence and stability.

To meaningfully address housing affordability and equity, government interventions must shift from short-term subsidies to sustainable financial instruments and legislative reforms. Inclusionary zoning represents another strategic lever worth exploring.

Internationally proven as effective, inclusionary zoning mandates developers to set aside a proportion of new developments for affordable housing, effectively blending market-driven housing supply with social responsibility. When carefully regulated to avoid stigmatisation and ensure quality parity, such zoning can diversify housing options and enhance social cohesion within communities.

Reforming investment incentives: introducing capital gains tax

Crucially, achieving these structural changes requires confronting the perennial political barrier of property as a primary investment vehicle.

The absence of a capital gains tax or similar wealth taxes in New Zealand incentivises speculative housing investment, inflating prices and diverting capital away from productive economic activities. Introducing a capital gains tax, excluding the primary family residence to minimise disruption, is an essential financial reform.

Though politically sensitive and with delayed revenue impacts, such a tax would eventually redirect investment towards productive sectors and housing affordability solutions.

A call for political courage and strategic vision

At a fundamental level, policy discourse must re-frame housing from being viewed merely as a market product to recognising it as a critical human need and social good. Housing policies must prioritise long-term societal benefits, community stability, and individual wellbeing above short-term market dynamics and speculative gains. This requires bipartisan commitment and ideological flexibility from political actors, transcending entrenched party position — market primacy on one side and state housing dependency on the other.

New Zealand's historical experience clearly demonstrates that home ownership, when strategically supported by the state and coupled with community-centric models, provides profound social and economic benefits. The country has solved these issues before, suggesting that the primary barrier today is political will, rather than economic feasibility. The post-war policy approach, combining government incentives, financial innovations, and local community-driven initiatives, can be adapted and scaled within the current economic context. Progressive home ownership programmes, expanded shared equity schemes, inclusionary zoning mandates, and strategic tax reforms collectively represent a viable and necessary policy pathway.

Ultimately, the party or coalition that boldly embraces these comprehensive housing reforms will secure not only immediate electoral support but also a lasting political legacy. Addressing New Zealand's housing crisis is more than economic prudence — it is a moral imperative.

The nation owes it to current and future generations to restore equitable access to housing, underpinning social stability, economic productivity, and genuine community wellbeing. As New Zealand has historically proven, a strategic, committed return to home ownership models and financial inclusion initiatives can, once again, make the country's housing system a global exemplar of fairness and opportunity.

NZ Household Tenure – Owners vs Renters (1986–2018)

- 1986: 75% owners · 25% renters

- 1991: 71.4% owners · 28.6% renters

- 1996: 70.5% owners · 29.5% renters

- 2001: 67.8% owners · 32.2% renters

- 2006: 66.6% owners · 33.4% renters

- 2013: 64.8% owners · 35.2% renters

- 2018: 64.5% owners · 35.5% renters

Major New Zealand Government Privatisations (1988–1999)

| Asset / Entity |

Sale Price (NZD million) |

Notes |

| Telecom Corporation |

4,250 million |

— |

| Housing Corp Mortgages |

2,410 million |

1991–1999 |

| Contact Energy |

2,331 million |

— |

| Petrocorp |

801 million |

— |

| PostBank (Post Office Bank) |

665 million |

— |

| Air New Zealand (initial stake) |

660 million |

— |

Combined Build & Land Cost vs Average Salary (1974–2024)

| Year |

Multiple of Average Salary |

| 1960 |

2.6× |

| 1969 |

3.5× |

| 1979 |

2.9× |

| 1989 |

3.9× |

| 1995 |

5.2× |

| 1999 |

4.4× |

| 2005 |

6.2× |

| 2009 |

6.8× |

| 2014 |

7.7× |

| 2020 |

11.2× |

| 2024 |

10.9× |