Annie Wilson, who brings extensive UK experience to her current role at Kāinga Maha in Christchurch, explains that Inclusionary Zoning and Inclusionary Housing's real strength lies in its ability to create mixed-tenure developments.

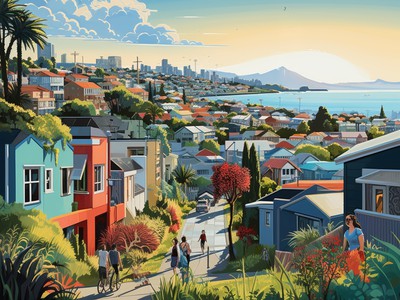

"It enables a diverse provision across a district area rather than new provision being in areas that perhaps may have higher concentrations already of social housing," she notes. The result is a more balanced housing landscape and, crucially, more sustainable communities.

The evidence against mono-tenure communities

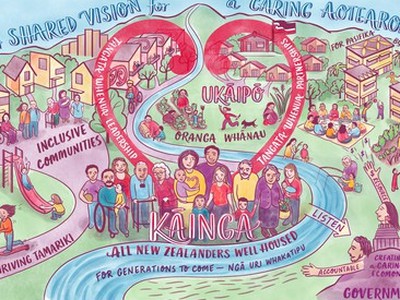

The case for mixed-tenure developments isn't based on ideology. It's grounded in decades of research demonstrating the adverse social consequences of concentrated single-tenure areas. Whether those concentrations involve private rental, social housing, or even owner-occupation, the lack of diversity creates unintended problems.

Annie points to compelling international evidence showing how mono-tenure neighbourhoods can undermine community cohesion. High concentrations of any single housing type can lead to social silos, limited social capital, and reduced opportunities for residents to thrive. Conversely, mixed-tenure communities create opportunities for diverse social networks, breaking down barriers and fostering genuine community connections.

The practical benefits extend beyond social cohesion. Mixed communities support local economies by ensuring a range of income levels, they provide housing for key workers who keep essential services running, and they create neighbourhoods that can adapt to changing demographics over time.

Addressing developer concerns

Inclusionary Zoning can be controversial, and Annie doesn't shy away from acknowledging the commercial realities developers face. However, she argues that opposition often stems from uncertainty rather than genuine viability concerns.

The key prerequisite for successful implementation is a clear, evidence-based understanding of local housing needs. Councils must demonstrate that failing to provide affordable housing will ultimately harm the existing community, particularly as new development drives house prices upward. When developers understand they're serving the community's genuine needs, the policy becomes easier to accept.

Yet evidence alone isn't enough. "What is absolutely required where you've got a policy for Inclusionary Zoning within a district plan is a clear test that it will ensure the viability of a local plan," she emphasises. Developers need certainty that the policy has been rigorously tested and won't render projects unviable.

Flexibility is equally crucial. Projects may require significant infrastructure investment such as new roads, expanded utilities, or other essential services. Successful Inclusionary Zoning policies balance multiple policy objectives, ensuring that affordable housing requirements don't inadvertently prevent necessary infrastructure development or make projects financially impossible.

"A key element to success is that certainty that a developer needs," she explains. Developers must know the policy requirements upfront when appraising projects or purchasing land, giving them confidence to incorporate affordable housing into their financial planning.

Delivery mechanisms: From homes to land to financial contributions

International experience demonstrates multiple approaches to delivering Inclusionary Housing obligations. In her UK experience, the most common requirement involves on-site provision — developers must build a specified percentage of homes as affordable units and transfer them to community housing providers or social landlords, such as CHPs in a New Zealand context.

These affordable homes might target different groups: social housing for those in acute need, affordable rentals, or progressive home ownership schemes for first-time buyers. The specific mix depends on local housing needs assessments.

Alternative mechanisms include providing land in lieu of built housing, allowing community housing providers or councils to develop it later. Some policies permit financial contributions when on-site provision doesn't make sense, perhaps because an area already has high social housing concentrations, or when the contribution can achieve better outcomes elsewhere.

"It's critical with that sort of policy that you have a very clear framework for using that financial contribution," she cautions. Councils must be flexible with developer negotiations and demonstrate they can deploy these funds effectively, with available sites and capable partners ready to deliver housing.

Leading by example: Kāinga Maha's voluntary approach

Annie's organisation, Kāinga Maha, has taken the extraordinary step of voluntarily adopting Inclusionary Housing principles despite no policy requirement. This decision reflects their fundamental belief that mixed, balanced communities represent the right solution.

"We take a people-first approach to property," she explains. "We look at a site, its context, try to understand the housing needs, the socioeconomics of an area, and how we as a developer can respond positively." While they operate commercially and must ensure developments remain viable, their measure of success isn't purely financial return — it's delivering developments that positively contribute to local housing needs.

As a charity, all profits and surpluses get reinvested for social good, enabling this distinctive approach. "We are a commercial developer but with a real social conscience," she notes.

Their Karamū development in Christchurch benefited from strong council support. Christchurch City Council provided relief on development contributions, which was a significant instrument enabling viable social housing delivery, and offered consent fee discounts for not-for-profit applicants. The council's community housing strategy provides clear strategic objectives, enabling Kāinga Maha to respond effectively to identified needs.

The importance of a national framework

A crucial distinction in the UK's success with Inclusionary Zoning lies in national-level support. Central government provides an absolute mandate through national policy, and a regulatory framework within the national planning framework.

Every single local council must demonstrate how they'll meet all housing needs in their district area — this obligation is enshrined in statute and planning policy. "Each local council is seen as having a strategic housing enabling function," she explains. They must evidence their housing needs across all groups — older people, first-time buyers, private renters — and establish policy frameworks setting minimum affordable housing levels and affordability criteria.

This top-down framework creates structural systems within councils, including dedicated teams for affordable housing delivery and planning control teams that test applications against policy targets. "You've got a structural system that all holistically contributes to that fundamental requirement to deliver housing that meets the needs of the local area," she observes.

The comprehensive approach prevents councils from avoiding their obligations and ensures resources and expertise exist at the local level to implement policies effectively.

A call to action for territorial authorities

Annie's message to New Zealand territorial authorities is clear: councils have a responsibility to meet the community needs of the people they serve. When housing is recognised as critical infrastructure, the mindset shifts fundamentally. She asks "Why would you not have a policy tool or framework to ensure the delivery of that?" Councils already understand their obligations to provide transport infrastructure, education facilities, and social care. Housing deserves the same consideration.

"When you see it as a key piece of infrastructure, just like transport, just like education, like social care, then you recognise the need to have a real clear framework to deliver against that," she argues.

The question for New Zealand isn't whether to adopt this approach, but how quickly councils can put the necessary frameworks in place.