Markdown Version

Dr Patricia Austin helped create New Zealand's most successful affordable housing programme.

Two decades on, she explains why the rest of the country should follow.

Understanding the fundamentals

Inclusionary Housing goes by different names depending on where you are. In the UK, it's Section 106 housing. In America, affordable housing requirements or density bonuses. But the core concept remains remarkably simple: when developers get permission to build, they deliver a certain proportion of homes as affordable. Patricia notes "It's a relatively simple mechanism used in a number of countries. The terminology alters depending on context."

What makes these systems work or fail often comes down to the legislative framework beneath them. The UK's town and country planning legislation balances social, economic, and environmental concerns equally. New Zealand's Resource Management Act focuses primarily on property rights and environmental externalities, with social considerations largely absent.

To build in the UK, developers must negotiate with councils to acquire development rights, and it's during these negotiations that affordable housing requirements enter the picture.

In New Zealand, by contrast, zoning changes essentially gift development rights to landowners without any quid pro quo. When district plans update zoning, property owners receive those development rights automatically.

She explains "In New Zealand, we have zoning. As soon as the district plan tells you the new zoning, you get given that development right without any asking for money back."

California for example offers another model. Despite having zoning similar to New Zealand, municipalities can require up to 15% affordable housing without legal challenge. Beyond that threshold, disputes head to court. It's a pragmatic compromise that provides certainty while addressing need.

The Queenstown Lakes success story

Her involvement with Queenstown Lakes District's Inclusionary Housing programme offers perhaps the clearest New Zealand example of what's possible. Working with consultancy Hill Young Cooper and colleague David Mead, she helped develop a programme that has delivered substantial affordable housing volumes.

The context made the need obvious. Queenstown's relative isolation created stark problems: young workers would arrive, work for five to seven years in the service economy, and want to stay to raise families. But they couldn't afford to buy homes. Even local construction workers lived in Cromwell, an hour away, driving in each morning.

The approach started with linkage zoning, connecting economic development directly to housing need. New ski fields, large housing developments, supermarket expansions, airport growth: all created jobs requiring workers who needed somewhere affordable to live. She notes "All the people who are going to be working in those economic activities have to live somewhere." Working with formulas drawn from overseas experience, the team calculated how many additional homes would be needed, what price brackets the market would deliver, and where council intervention made sense. Running the proposal through the council's RMA lawyer, they knew it would land in the Environment Court. She points out "It was inevitable."

The retention challenge

One of Patricia's most striking examples involves a well-intentioned developer in Queenstown who subsidised sections for his workers to build affordable homes. His workers gratefully built houses, then sold them, flipping for profit. One cycle, and the affordability vanished. "Without strong mechanisms to retain affordability, you might as well not bother."

Time-limited affordability requirements don't work. Auckland's Special Housing Accords included five-year affordability periods, now long expired. Maryland, one of the first American states to implement large-scale Inclusionary Zoning, capped requirements at 20 years. That was 40 years ago. Those restrictions have all lapsed.

True solutions require perpetual affordability or robust recycling mechanisms. If someone purchases an affordable home, sale proceeds must return to community housing providers to purchase replacement housing.

Community land trusts offer particularly strong retention mechanisms. Households purchase houses but not land, which remains in community ownership through leasehold arrangements. Queenstown's 'secure housing tenure' functions similarly. The community housing trust owns land, issuing renewable 99-year leases. When families need to leave, they sell improvements back to the trust at original cost plus CPI adjustment.

The housing needs assessment foundation

For Inclusionary Housing to work, it must rest on solid understanding of community need. Patricia developed a draft needs assessment framework for the 2007 Affordable Housing Enabling Territorial Authorities Act, legislation that lasted only 12 months before the incoming Key government repealed it.

She emphasises "How many people are in housing need, how many people in the future will be in housing need, what price brackets are you looking at, what types of households?" The data required is readily accessible: census information, QV property data, step-by-step analysis that councils can manage.

She also notes that "Matching demand against what's available at different price points basically tells you what the problem is."

Legislative barriers and opportunities

New Zealand's current RMA creates significant barriers to Inclusionary Housing implementation. Voluntary approaches using incentives don't work because of the 'permitted baseline' problem. When developers receive height bonuses for including affordable housing, neighbouring property owners successfully argue they're now entitled to the same height, regardless of affordable provision.

There is potential for paths forward to emerge. First, amend the Affordable Housing Enabling Territorial Authorities Act.

Second, incorporate social considerations directly into RMA legislation. Third, follow California's model: establish an accepted norm (perhaps 10% or 15%) that councils can require without legal challenge.

Current RMA reform presents timing opportunities. Central government enablement would prevent individual councils from standing alone facing legal challenges, as Queenstown has. National frameworks with local flexibility could address the reality that Wellington's housing market spans multiple territorial authorities with workers commuting across boundaries.

The UK's residual value approach

Section 106 in the UK demonstrates how systematic value capture can work. When developers approach councils with plans, negotiations begin around a residual value calculation. Councils assess land costs, development costs, and reasonable profit margins. Whatever remains goes towards affordable housing requirements. She adds "There's a good logic to it. It's transparent and it's accountable and you can see clearly."

The system captures value because the development right itself creates the opportunity. London boroughs negotiate requirements up to 40% in some areas.

Research from Australia's Professor Nicole Gurran examined what happened when New South Wales essentially said developers could build anywhere. The impact on affordable housing delivery? "Minute amount," she reports. Market-driven approaches alone simply don't deliver affordable housing for low and moderate-income households.

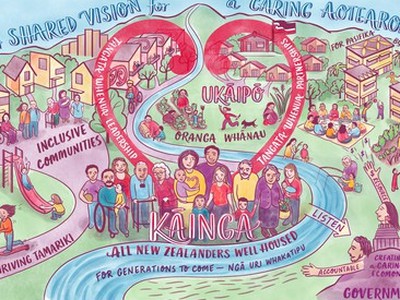

Housing as community context

Beyond policy mechanics, Patricia returns repeatedly to a fundamental truth: housing is more than physical structures. Her examples from Auckland's Kāinga Ora redevelopments illustrate the point powerfully.

Families offered well-designed homes in Manurewa face impossible choices. The house is decent, but all their connections remain on the isthmus. Some Pacific families have parents who live in Manurewa whilst children stay with grandmothers in original suburbs near schools and churches. She emphasises "Housing is more than the actual house. Housing is the local community context. It's where granny lives...that is a bit we haven't quite managed to get ourselves to understand. And that's particularly true for more vulnerable families who are only just managing to survive economically."

This understanding shapes her advocacy for using cleared Kāinga Ora sites differently. Rather than waiting indefinitely for private sector development that won't deliver sufficient returns, councils should work with community housing providers to build for disrupted local communities.

The economic development reframe

Asked whether Inclusionary Housing is worth trying in New Zealand, Patricia reframes the question strategically. Rather than leading with mixed-income community goals, she'd emphasise economic development opportunities.

She states "If I was a local policymaker or a politician, I would be really interested in ways to kickstart the construction industry," she explains. Auckland's private sector construction companies have made clear they're not doing much more development because there's insufficient profit."

But combine community housing providers who can access additional funding, cleared Kāinga Ora sites not currently being developed, and a skilled workforce needing work, and suddenly you have an economic development opportunity.

She adds "If you presented this as an economic development opportunity, then said 'and by the way, this could deliver affordable housing', councils understand that."

"I don't care what the motivation is," she admits pragmatically. "If you end up with good quality housing in existing communities that community housing providers can retain and actually bring some displaced community people back into it, it's a win-win for everyone."

Beyond magic bullets

Patricia resists framing Inclusionary Housing as New Zealand's single solution to affordable housing challenges. In the current tight fiscal environment, with government essentially removing its balance sheet from large-scale affordable housing supply, Inclusionary Housing represents one of few options that might significantly move the dial. "I don't think it's a magic bullet. I think it's part of the package," she emphasises.

Developers face genuine difficulties. But significant speculative land value increases create value worth capturing. If community housing providers can guarantee purchasing 10% of stock at subsidised rates, that provides developers with certainty and assured sales.

Central government might contribute a bit, developers a bit, councils a bit through sites they're not using. Creative combinations of modest contributions from multiple sources can add up significantly.

Learning from Queenstown

The Queenstown Lakes' experience demonstrates what's achievable. Despite ongoing opposition and litigation, the programme has delivered substantial affordable housing, created community acceptance, and enabled essential workers to remain in the district contributing to community life.

The programme's evolution from voluntary contributions through linkage zoning to formal inclusionary requirements shows how incremental progress builds momentum. Starting with economic development arguments made the case more accessible than abstract mixing goals.

Twenty years on, Queenstown Lakes Community Housing Trust stands as New Zealand's exemplar, proof that inclusive housing works when well designed, properly retained, and genuinely integrated into communities. The question isn't whether New Zealand can do this. Queenstown already has. The question is whether the rest of the country will follow?