Emily Irwin: A planner's perspective

Why Market Forces Fail in Resort Towns: A Strategic Housing Planner's Case for Inclusionary Zoning

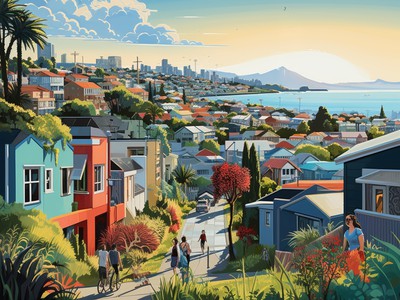

Standing in Queenstown, one of New Zealand's most expensive housing markets, Emily Irwin confronts a stark reality: free-market supply alone cannot solve affordability in high-value resort towns.

As Strategic Housing Planner at Queenstown Lakes District Council, she's witnessed firsthand how unregulated markets can push average house prices toward the millions, a trajectory that mirrors Aspen, Colorado, where homes average $13 million."We can't just rely on the market," Emily explains. "That's not going to work. We're seeing that it's not working and it's only going to get worse."

Her argument challenges orthodox economic thinking that increased supply automatically delivers affordability. In resort communities where global wealth concentrates, traditional market mechanisms fail to provide homes for the workers who keep these towns functioning. The consequences ripple through every sector. She noted "Teachers leave because they can't find housing." Emily's partner, a high school teacher, sees massive staff turnover. Local businesses face an estimated $200 million in extra costs from workforce turnover. Nurses become scarce. Social connections fracture as friends must leave town. "It affects everybody else who might have a secure home," she notes.

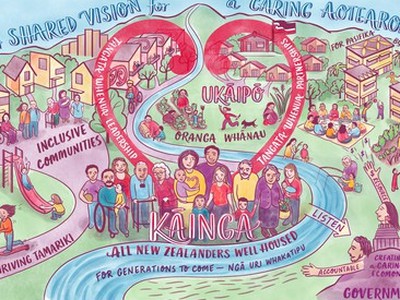

At the heart of the crisis lies a cultural question: are houses for living in, or for building wealth?

For two-thirds of New Zealanders who own homes, this question cuts deep. "It's very challenging in New Zealand because we've just got this cultural background of investing in housing as our main asset," she notes. This fixation has redirected economic energy away from productive businesses and toward property speculation. Inclusionary Housing mechanisms offer an alternative pathway.

By capturing land from new developments for perpetual affordable housing, the approach distributes workforce accommodation across diverse neighbourhoods rather than concentrating it in distant, cheaper areas. "We're not going to have a ghetto," she emphasises, contrasting this with purely financial approaches that risk creating isolated affordable housing zones. But technical solutions aren't enough.

E

mily believes shifting the public conversation, expanding what's politically acceptable, is crucial for enabling bold policy action. "We need everybody to be on board with that to enable us to do that politically," she says, invoking the concept of the Overton window.

Her message to wealthy residents and developers is direct: everyone can contribute, whether through philanthropy or simply supporting conversations about housing as community infrastructure rather than investment assets.

The alternative, a Queenstown where only millionaires can afford homes, would destroy the community's ability to function. "Housing is a critical piece of infrastructure really for communities." Emily concludes. "It enables communities to work." In her view, recognising this fundamental truth represents the first step toward building housing systems that serve people rather than portfolios.